“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” Donald Trump said at the kickoff of his presidential campaign in 2015. "They're bringing drugs," he said. "They're bringing crime. They're rapists," allowing that "some, I assume, are good people."

But at one time, workers from Mexico were called “absolutely essential to the survival” of some U.S. industries – and brought into the country by the millions, with the approval of the federal government.

While immigrant workers have become inextricably linked to the story of the United States, our story begins in 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the “Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program.” It included a guest-worker agreement between Mexico and the U.S. that came to be known as the “bracero” program – because people worked with their brazos, or arms.

While the second World War raged, many countries – including the United States – struggled to meet the demands of the machinery of war, and fill the labor vacuum left by men sent to the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific. Labor was in such short supply that women left their homes and office buildings, and picked up rivet guns and worked in factories.

But the fields were left vacant.

The Women’s Army of America, which was modeled after a British program, recruited about 3.5 million women to work in agriculture. But it wasn’t enough.

It was this need for agricultural workers that prompted the U.S. and Mexico to create the bracero agreement.

Dr. Enrique Armas Arévalos, a professor at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo in Morelia.

Dr. Enrique Armas Arévalos, a professor at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo in Morelia.

U.S. businesspeople were very specific about their needs because they wanted to protect the jobs of U.S. workers,” says Enrique Armas Arévalos, a professor at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo.

The U.S. government offered braceros the same wages it would pay American workers. Workers were also offered paid transportation to and from the their hometowns, and access to health care and retirement accounts that would be distributed through Mexican banks.

Almost 5 million Mexican workers signed up. My late grandfather was one of them.

I never got to record the details of my grandfather's bracero experience, but other accounts of bracero work are pretty consistent – and as with any program, there were things that worked and things that didn’t.

But one thing that was never supposed to happen was the mistreatment of workers.

Jose Natividad Avila Medina was a bracero, and he says he was treated like an animal – like cattle – and not like a guest.

His interview is part of an oral history project produced by the University of Texas at El Paso. He recalls arriving in the U.S. by train with thousands of other workers.

The line of workers at the border stretched for more than half a mile, he says. Everyone was ordered to strip completely naked. While still in line – and still naked – the workers were ordered to bend over so that officials could do cavity searches.

Jose Natividad Avila Medina came from Michoacán, the same as my grandfather. Nestled in the west-central region of Mexico, throughout the 20-plus years of the Bracero program, Michoacán provided the most workers.

That’s where I met 77-year-old Elías García Castro and his wife Rosa Nava Castro.

“I worked picking lettuce on my first trip and then strawberries,” Elías says.

Elías has always been a farmworker. He still raises small farm animals, like the turkeys roaming around us. But when he was in the States, he says the work was brutal. “We weren’t allowed to stretch,” he says.

Picking lettuce meant he had to walk hunched over from sun-up to sun-down. His wife Rosa remembers that he was in excruciating pain daily. He told her about a chorus of men wailing in pain when they stood for a bathroom break. They couldn’t even sit on the latrines. It was agony.

Today, Elías walks with a cane. Rosa thinks it’s because his back was permanently damaged during his bracero experience.

Texas was excluded from the program for the first five years. Mexican authorities said they feared for the workers’ safety. The state was openly discriminatory to Mexicans; this was a time when restaurant windows had signs that read “no dogs, no negroes, no Mexicans.” Despite its concerns, the Mexican government eventually allowed Texas into the program.

Richard Vogel recalls the bracero workers in Texas. Back in the 1940s, he grew up with his family on a dairy farm outside of El Paso, in a small town called Ysleta.

His chores included shooting farm rats. He would later sell them to his favorite bracero. “He paid me a nickel each because they used them for food,” Vogel says.

As nasty as it may sound, Vogel says he thought of it as a step up from the dog food he saw ranchers feeding the braceros who worked for them.

Even worse was the treatment at the processing center in Fabens, Texas.

“The Mexican men were deloused,” Vogel says. “I couldn’t believe it – because they were put into a sheep-deep tank – total immersion in a DDT-Chlorodyne solution – to kill the lice. But what hit me is they had barbed wire on this enclosure in Fabens, and it looked to me like a concentration camp.”

The treatment of braceros became such a point of contention between Mexico and the U.S. that the program was temporarily suspended in 1948. Congress said it was because the “labor emergency” was over because the war had ended.

When the bracero program was suspended, Mexican workers still came to the U.S. They made 20 times what they could make in Mexico.

Victoria DiFrancesco Soto, an immigration expert at UT-Austin’s LBJ School of Public Affairs says this time they entered via the Rio Grande.

“That’s where that term 'wetback' came from in, the 1940s,” she says.

Ranchers needed workers, and Mexican workers still wanted higher-paying U.S. jobs. So Operation “Drying out the Wetbacks” kicked off.

“'Drying out' in today’s parlance, and in a non-slurred category, would be 'normalizing' your legal status,” DiFrancesco Soto says.

Border Patrol would show up at a field, round up the unauthorized workers, drive them to the border, get them to sign temporary contracts, turn around and bring them back to the field where they were picked up originally.

Everyone was complicit: the workers who entered the U.S. illegally, the ranchers who hired them illegally, the Border Patrol who normalized the process, the U.S. government that turned a blind eye to an abusive system, the Mexican government complicit in the abuse, even the Mexican banks that failed to disburse the worker’s retirement money – half a billion dollars by today’s standards.

In 1951, Congress reinstated the bracero program as Public Law 78. It lasted through 1964. But its legacy lived on in my family.

The bracero program gave my mom seven siblings – all born consecutively, like clockwork during the summer. While my grandfather was a bracero, as part of his contract, he returned to Mexico every year after the fall harvest. By the time he returned to the U.S. for a new planting season, my grandmother would inevitably be pregnant.

Michoacán and the west-central region of Mexico have been forever changed too. The region is still rich in agricultural land. As I flew in to meet Elías and his wife Rosa, Michoacán looked 50 shades of green.

The Open Secret Of Undocumented Construction Labor

Texas is home to one of the largest immigrant populations in the country, the majority of which originally came from Mexico.

That’s not just because Mexico is Texas’ neighbor, but also because for decades, Texas held labor agreements that brought Mexican nationals over to work.

When the Bracero program – one of the largest guest worker agreements in the history of the country – first began, the emphasis was on getting agricultural workers to the U.S. Today, we continue to employ immigrants – both authorized and unauthorized – in every sector of the economy. But the industry with the most unauthorized workers in Texas isn’t agriculture any longer.

It’s construction.

Before Hurricane Harvey hit, Texas had the most construction projects in the country. Rebuilding from Harvey will mean even more work. And within Texas, Houston has the most construction projects in the state. It’s a well-oiled $54 billion industry.

Stan Marek is the CEO of an interior construction firm. Clad in a hard hat and safety vest, he takes me on a tour of the dry wall and metal framing work his company is doing for Texas Children’s Hospital.

To get to the 16th floor, we ride a cage attached to the outside of the building. As we talk, Marek often points to his worker’s high standards for safety. He’s clearly very proud – but what he’s the proudest about is a commitment he made years ago to never hire unauthorized workers.

Stan Marek, CEO of Marek Brothers Systems, at at the Texas Medical Center construction site in downtown Houston.

Stan Marek, CEO of Marek Brothers Systems, at at the Texas Medical Center construction site in downtown Houston.

“Morally, I cannot do that,” he says.

But Marek is not the only contractor at the children’s hospital. It’s very likely that his workers are among the relatively few construction workers who are authorized to work in the country.

“Up to 50 percent of the construction work force in the state of Texas is undocumented labor,” says Jose Garza, executive director of the advocacy organization Workers Defense Project.

Jose Garza of the Workers Defense Project. Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon/KUT News

Jose Garza of the Workers Defense Project. Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon/KUT News

The 2011 study he’s quoting is from his organization and the University of Texas at Austin. Some in the industry, however, estimate that number is even higher. In some construction crews, it’s hard to find a single authorized worker.

So what could happen if all these workers were deported?

Rafael is a short man with sun-scorched skin the color of cinnamon. (It’s not his real name – he asked me not to use his real name to lessen the risk of deportation.)

Rafael is an unauthorized construction worker.

“We’re on the campus of the Texas State University in San Marcos,” Rafael says in Spanish as he points to some of the buildings. “On this college campus, my team built the student dorms, several gymnasiums – we laid the foundation of all of these buildings and their parking lots as well.”

During the 20-plus years that Rafael has been in Texas, he says he’s never been unemployed. That’s how much construction is booming in the state.

“I’ve been busy building Texas,” he says.

Every hospital, every school and every highway in Texas has benefited from undocumented labor, either directly or indirectly. Yet the mere presence of people like Rafael in this country is believed by many to be a crime.

“The system is broken,” says Marek. He says he remembers the moment it broke – when “the IRS allowed you to call your employees ‘independent subcontractors.’”

Not everyone can be an independent subcontractor; there’s a 20-point criteria to meet. Marek thinks it was tailor-made for unauthorized workers, and that’s why construction workers fit the criteria so well. He says employers exploit that loophole, “because you basically could put the responsibility of payroll taxes on [the independent subcontractors], which would become self-employment taxes,” Marek adds.

Employers who hire independent subcontractors, or “subs,” get to keep what they’d otherwise pay in payroll taxes. There’s no need to pay them benefits or overtime, and employers can even skip checking their subs’ immigration status. And it’s all legal.

“It’s badly misused,” says Marek. “So many companies have looked for that loophole.”

There are about one million construction workers in Texas. The study done by UT and the Worker’s Defense Project estimates that at least half, if not more, are unauthorized. But while they are off the books, the IRS still considers them part of the tax rolls: four and a half million construction workers filed income taxes in the U.S. last year.

Rafael has been filing his taxes for about 20 years, ever since the IRS created a special tax bracket for unauthorized workers in 1996. When asked why he does it, Rafael is at a loss for words.

“I don’t know,” he says. “It’s complicated.”

It is complicated. Rafael will never get a pension or Social Security out of it. He can’t get Medicaid or other benefits the way authorized workers can.

“On the one hand, I don’t exist in this country,” he says. “But if I don’t pay taxes, that will alert the authorities and raise a red flag. I don’t get it – how come I’m invisible for some things but not for others?”

The unauthorized labor force in Texas may not exist on paper, but everyone knows it’s there. Everyone agrees immigration policies are broken, but everyone knows our state depends on unauthorized labor.

It’s an open secret – or as we say in Spanish – es un “secreto a voces.”

Could Texas afford to halt that flow of money in exchange for complying with new state laws and beefed up federal immigration enforcement? And if the U.S. were to deport half a million construction workers like Rafael, would that affect everyone else in the country? Bill Beardall, clinical law professor at the University of Texas, says it would.

“Everyone in Texas is the beneficiary of undocumented labor,” he says. “If you live or work in a building built in the last 20 years, you’ve almost certainly been the beneficiary of the undocumented labor that contributed to that construction. If you drive on roads and highways in Texas, you’re driving on roads that were built partly with undocumented labor.”

He goes on to name more instances: if you shop at a big box store, if you eat out, if you have kids and someone else cares for them, if you’ve been hospitalized. “Every phase of normal life in Texas benefits form the hard work and often the exploited work of undocumented immigrants,” Beardall adds.

When I left Houston, I was able to leave behind the beeping, pounding and humming sounds of construction. But Beardall’s words echoed over and over: I am the beneficiary of unauthorized labor.

Deportations on any scale could affect me.

And you.

Deportations And The Domino Effect On Texas Schools

Regardless of the weather, signs of fall are here in Texas.School is back in session, football has returned, and, as kids return to class, a slate of new state laws are set to take effect.

And despite most schoolchildren in Texas being U.S. citizens – 96 percent, by our count – the effect of deportations could soon be felt in schools across the state.

Along with the increase in federal deportations under the Trump administration, the implementation of one of Texas’ new laws – Senate Bill 4, the so-called “show-me-your-papers” law passed this last legislative session – could drastically alter Texas schools.

SB 4 was slated to go into effect September 1, until a judge temporarily stayed a portion of the law. The state has vowed to appeal, and, depending on the outcome, schools could be greatly affected – because when parents are deported, schools lose a ton of children.

At an elementary school in Edinburg, close to the Texas/Mexico border, there’s nothing that indicates the immigration status of its students.

Former Texas Education Commission Michael Williams. Filipa Rodrigues for KUT News

Former Texas Education Commission Michael Williams. Filipa Rodrigues for KUT News

Michael Williams, former commissioner of the Texas Education Agency, says that’s by design.

“We are not allowed to ask that question,” he says.

Since 1982, K-12 students have been able to claim the benefit of the Equal Protection Clause.

“There’s a United States Supreme Court Case (Plyler V Doe) that prohibits school officials from asking any student what their immigration status is,” Williams says.

Without that data, it’s hard to know how many children are undocumented or have undocumented parents. The TEA reports that last year, Texas had almost 5,500,000 children enrolled in schools. And the Pew Research Center says that about 13.4 percent of school children in Texas have parents who are unauthorized. That adds up to 737,000 kids whose parents are at risk of deportation - roughly the population of Fort Worth.

But while the exact numbers are unclear, one thing we know for certain: most parents who get deported take their children with them.

The roots of all these mixed status families run back to the Bracero program – a 20-year guest worker agreement between Mexico and the U.S. Many of the Mexican workers came from Guanajuato, one of the most beautiful states in country. Its Spanish Colonial architecture has earned it a World Heritage designation from the United Nations.

But 16-year-old Gladys Martinez Garcia hates it there.

She says it’s not home, and dreams of going back to her father who’s still in the U.S. But after Gladys’ mother was deported, she made her and her two sisters join her in Mexico.

Gladys was only nine then, her sisters a little older.

“I told her that I wanted to go back because I don’t like it here that much, but I couldn’t do a thing,” Gladys says.

Her mother, Rita Garcia Martinez, says the girls suffered through the process.

“Our family’s been broken,” she says. “The girls used to cry every evening, and count the days until they could go back.”The Martinez Garcia girls are just three out of thousands of children that this region is expecting to receive along with their deported parents.

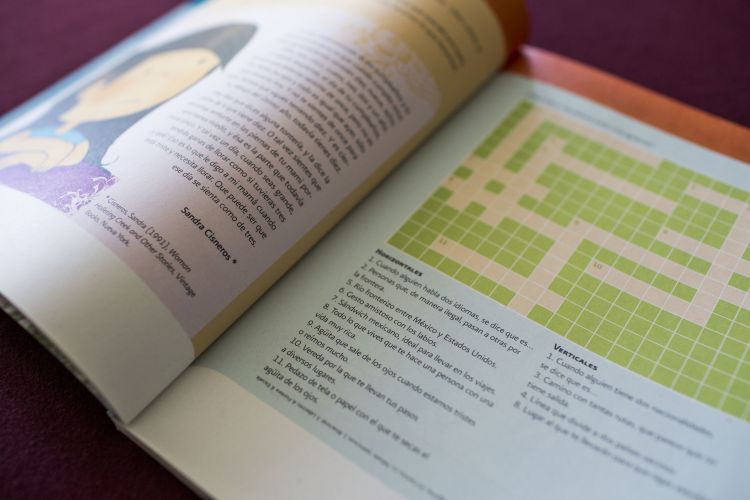

Ricardo Sanchez Carrillo, who’s in charge of bilingual education in the neighboring state of Michoacán, says the governments of Mexico and the U.S. have told him to get ready for about 5,000 kids to arrive in Michoacán this year.

“The situation is very complex,” he says. “The school systems in the U.S. and Mexico are very different. And the culture is different too. They miss the food, most of the children do not speak Spanish and therefore face discrimination, and their psychological trauma is huge after their deportation or their parents’ deportation.”

Ricardo Sánchez Carrillo with Programa Binacional de Educación Migrante in Morelia.

Ricardo Sánchez Carrillo with Programa Binacional de Educación Migrante in Morelia.

Schools in Texas could lose a ton of children. We know this because both the U.S. and Mexican governments are talking about it. But if schools in Texas lose children, former TEA Commissioner Williams says that also translates into lost school funding. He says that on average, “One child responds to about 8,000 in federal and state dollars to a campus.”

So if eight kids were to leave the school system, that alone would account for a loss of $64,000.

“That’s about what you pay a teacher,” Williams adds.In some Texan school districts, the Hispanic student body population is huge: like Rocksprings ISD with 58 percent, or Alice ISD with 84 percent, or even Progreso ISD with 97 percent.

“So, you wouldn’t necessarily have to work real hard to get to eight students or 16 students or 24 students that would be removed from school,” Williams says. “That could have real financial consequences.”

There are dozens of small school districts in Texas that could be severely affected, like Cotula or Santa Maria. Even large districts like Austin and Houston could feel the consequences.

“It may be easier to say what districts might not be affected,” Williams says.

The loss of sales and property taxes could also follow, as those deported parents would stop paying – and in Texas, property taxes pay for schools.

It’s a domino effect.

Political scientist Tom Wong says that, if SB 4 further ramps up federal deportations, the biggest challenge wouldn’t be to schools, but the state.

Wong teaches at the University of California San Diego, but his forte is in crunching numbers. Earlier this year, the City of Austin hired him to estimate the negative effects the city would face if deportations were to escalate significantly under SB 4.

He focused on the law’s effects on public health, public safety and education. When it came to schools, Wong compiled the number of reported absences in the week after Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids in Austin earlier this year. He then compared those absences to the same period of time last year.

In Austin ISD, absences increased by 152 percent.

“As interior immigration enforcement ramps up, the concern is that there’s a chilling effect … on the day-to-day behavior of undocumented immigrants,” says Wong.

That could translate into more kids missing school. A year ago, 14,000 Austin children were absent in February; after the ICE raids this year, 37,000 were absent. And all of those absences were of Hispanic children.

And since schools get paid per kid, per day, absences cost money. So the loss – estimated at over $1 million – was felt immediately. Wong also looked at the effects similar laws have had in other parts of the country, like SB1070 in Arizona, HB56 in Alabama and Prop 187 in California.

“And so, the dominos start to fall,” Wong says, noting that, as increased absences affect graduation, “based on this analysis – we can then see how this can impact the college educated and college trained for the City of Austin, as well as the state of Texas more generally.”

Former education commissioner Williams says that “nobody thought about this when people were proposing the legislation or debating it.”

“And so, yeah,” he adds. “I am hoping and praying we don’t get to this.”

If the census data is correct, the children playing in Edinburg or Austin elementary school playgrounds are Americans; only four percent are not.

But they are American children that could be gone.

How An Underground Economy Serves Unauthorized Workers

Texas’ unemployment rate is currently 4.3 percent, in line with the national average. The housing market is as robust as it’s ever been. While the “Texas miracle” has seen some slight diminishment, it still outperforms many other states.

But if you think that’s the whole story on the economy, think again.

There are more than 1.65 million unauthorized residents in Texas. They live here (many for over a decade), they work here, and many of their children were born here.

That also makes 1.65 million consumers of a carefully-crafted economic system, built just for them.

“Consumers make up 70 percent of our economy as measured by the gross domestic product,” says Michael Brandl, an economist at Ohio State University. “The more consumers we have – consumers that are spending – the faster our economy is going to grow,” he says. “So there’s a huge incentive to try to get as many consumers as possible, and when they’re spending those dollars… nobody is going to check, ‘What exactly is your immigration status?’”

That same message is echoed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Just a couple of months ago, Dallas Fed president Robert Kaplan spoke at the Council of Foreign Relations in Washington. There, he said that President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown is starting to have a negative effect on the economy, because immigrant consumers are staying home in fear of deportation.

Brandl, a former economics professor at UT’s McCombs School of Business, says Texas consumers are taken seriously because there’s no state income tax. Consumers are at the core of the Texas economy.

“The undocumented workers still pay taxes,” says Brandl. “When they go to the store no one asks them, ‘You’re not a citizen? You don’t have to pay state sales tax.’”

If they own a home, they pay property taxes. If they rent a place, property taxes are passed on to them in rent. Many pay income tax through the Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, or ITIN, that the IRS created about 20 years ago. In 2016, 4,500,000 unauthorized workers in the U.S. reported their taxes to the IRS alongside American citizens.But in order to have an income they can report, unauthorized immigrants need four things.

First, they need an ID – which usually ends up being a fake one.

College student Catherine Tellez guided me through the process of getting a fake ID. To my untrained eyes, hers looks completely real. She says the first trick is to pick a state that’s not Texas.

“Texas IDs are like top of the line,” she says. “My brother-in-law is a bartender and he’s like, ‘Oh, you can feel a Texas ID, you can feel that they’re fake.’” So Tellez went with South Carolina.

A counterfeit South Carolina ID. Joy Diaz/Texas Standard

A counterfeit South Carolina ID. Joy Diaz/Texas Standard

The second step, she says, is to get your stuff ready – take a passport-style photo at home or a nearby drugstore, then take a photo of your signature.

Afterwards, you get online – Tellez says you can just Google “good fake IDs” – and you pay through Western Union or via Bitcoin. A couple of weeks later, you’ll get your very convincing fake ID, made in China, that allows kids like Tellez to get a drink at a bar.

But for people like Rafael, fake IDs allow him to get a job.

Rafael works in the construction business. (It’s not his real name; he asked not to use it, to lessen his risk of deportation.) He says people like him – who are unauthorized to work in the country – can manage a quasi-normal life if they manage to get three more things on top of an ID.

“One is a phone,” he says in Spanish. “But we can’t go through companies like Sprint or AT&T.”

Technically speaking, anyone (including Rafael) can get a phone from a company like AT&T – just as long as it’s through the backdoor with a prepaid plan. Cricket, the largest prepaid phone company in the U.S., is owned by AT&T. And Sprint's prepaid plans are sold at Wal-Mart, no social security number required.

So if unauthorized immigrants aren’t welcome in our country, why do these huge multinational companies cater to them?

“Because ultimately we want them as consumers,” says Brandl. “And the market is kind of responding to that. When there is a need for something, a market is going to develop for that thing whether it is legal or illegal, just like there was a market that developed during prohibition.”

That’s why the car business is also a part of this underground economy – the second thing on Rafael’s list.

People like him need cars, but they can’t get them through the regular channels. When you’re unauthorized, most banks won’t give you a car loan.

That said, there are dealers that will extend undocumented immigrants credit for buying cars. But they tend to charge a premium price, since they know they could get in trouble selling cars to people like Rafael.

He could’ve bought a used car from these kinds of dealers, but instead decided to pay for two vehicles that he doesn’t own. The titles are under his sister’s name, who’s authorized to be here.

The third and last thing on Rafael’s list is a place to live. In his case, it’s a mobile home. The cost of a traditional home makes it inaccessible.

“The interest rate for me would be too high,” he says. “I simply can’t figure out a way to buy a brick and mortar one.”

There are banks that accept ITIN numbers in lieu of social security numbers, but mostly for cash transactions – ITIN numbers were, after all, created by the IRS to enable unauthorized workers to pay taxes. So mobile homes have become the de-facto home-ownership solution for many undocumented immigrants.

And mobile home parks are big money makers. The business is so good that Warren Buffet, one of the richest men in the country, owns mobile home companies in Texas.

And while the mobile home market is drying up in the northern part of the country, it’s thriving in the south and west. California and Texas have the most of any state, a combined 20 million-plus units. Texas and California also happen to be the two states with the largest number of unauthorized immigrants.

That’s why business owners I spoke to told me off the record that increased deportations – and the prospect of even more to come – are making them anxious. Politicians may be against illegal immigration, but businesses are not against profits.

Debate continues on whether a secondary cash economy is good or bad for the overall economy. After all, undocumented immigrants are not only consumers of goods, they’re also consumers of services.

In 2014, unauthorized immigrants are believed to have contributed $178 billion to the nation’s economy. That’s why we keep the door open – it may not be the front door, but we seem to be doing fine letting them in through the back.

HELP WANTED, GET OUT

Reporter/Producer: Joy Díaz

Photographer: Gabriel Cristóver Pérez

Researcher: Lucía Benavides

Web Editors: Wells Dunbar, Shelly Brisbin

Logo Design: Ashley Siebels

Additional Photo Credits:

File photo of braceros workers, courtesy of Humanities Tennessee

Photo of Texas State University in San Marcos courtesy of Flickr user Rain0975, under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Photo of figure in silhouette, Jon Shapley for KUT News

Photo of trucks in impound lot, Mose Buchele/KUT News

Photo of mobile home lot, Miguel Gutierrez Jr. /KUT News

"Help Wanted, Get Out" was funded with the generous support of The International Women's Media Foundation.

Audio, text and original images copyright 2017, Texas Standard. Learn more about Texas Standard, the national daily news show of Texas.