UNIDENTIFIED:

How Kids Can Age Out of Texas Foster Care Without Documentation

When you hear about someone in the United States without documentation, you may think of an immigrant. It seems almost inconceivable that an American would struggle to secure their birth certificate, Social Security card, or state identification. But it happens – and it happens most often to some of the state’s most vulnerable children – those in the foster care system.

Amber Meyers was sitting outside of the George Washington Carver Museum in East Austin on a warm evening this past July. Meyers, who goes by the name “Gypsy,” is currently homeless, and the museum’s illuminated plaza and benches give her a place to rest. She chose her moniker because she is not actually sure what her legal name is. Gypsy, who was once in the Texas foster care system, does not have a copy of her birth certificate or know the names of either of her biological parents.

She explains that getting identification has been a struggle, because without one piece of identification, it is hard to get others.

“I don’t have ID, I don’t have a Social Security card. In order to get [a] Social Security card you have to have an ID,” Gypsy says. “In order to get a birth certificate, you have to have an ID. But, you can’t get an ID without a birth certificate.”

Gypsy aged out of foster care about a decade ago, yet her struggle to secure identification is still relevant to children in the system today.

The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services or DFPS, is legally required to ensure that all children in foster care receive a birth certificate, a Social Security card, and a state identification card, by the time they are 16 years old. Caseworkers request these documents on behalf of children, and DFPS has ( Courtesy of Tymothy Belseth C eligibility specialists who work to obtain birth certificates, for example. However, not all children end up getting these identification documents.

DFPS spokesperson Patrick Crimmins tells Texas Standard “we understand that there will be times that youth leave foster care without their birth certificate or other essential documents – for a variety of reasons.”

One of the reasons he cites is children exiting care without notifying DFPS.

Crimmins also points out that obtaining a birth certificate for a foster child is especially challenging when she or he is born out of state.

“Out-of-state birth certificates are more challenging to obtain as there is no cooperative agreements between states and at times require submitting court orders,” Crimmins says.

Over the past six fiscal years, an average of 1,261 young people have aged out of the system annually. The agency does not currently track how many of these children may be leaving the system without their vital documents in hand.

Crimmins says the agency plans to begin keeping this data though.

“We are in the process of updating our Child’s Plan of Service to track if a youth received their required document[s],” he says, “This change is being made to our database, the state’s Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System (SACWIS) – known as IMPACT in Texas.”

Much like, DFPS, state lawmakers, researchers and nonprofits are working to ensure that all children in Texas foster care receive the identification documents to which they are legally entitled. In fact, many of these stakeholders have been working together on this issue. Sarah Crockett, the public policy coordinator for Texas CASA, says her organization has been coordinating a work group that includes attorneys, DFPS, and the Texas Department of Public Safety.

“We’ve all been working together pretty well for the last couple of years trying to break down all of the barriers to children and youth in foster care getting their birth certificates and IDs, hopefully before they turn 18, but ideally we’d like them to have that before they turn 16,” Crockett says.

Texas lawmakers are also working on this issue. State Rep. James White, a Hillister Republican, filed a bill this legislative session that seeks to ensure foster and homeless youth are able to get identification more easily. Among the things the bill seeks to do is exempt foster youth from paying fees for a driver’s license, for example. He tells Texas Standard having identification is vital because “you can’t vote without identification. You can’t even get on a plane.”

Gabriella C. McDonald, pro bono and new projects director with Texas Appleseed, explains that not having identification is a barrier for current and former foster youth, and the process of obtaining it can be disheartening.

“They’re going to get frustrated. They’ve already been sent from one place to the next place to the next place to do things,” McDonald says. “And if you’re going to be sent to the DMV and then realize you need to go to the Social Security office and then you don’t have transportation to get between those two places, you’re going to give up really quickly.”

McDonald says that without identification, former foster youth are vulnerable, and it can expose them to human trafficking.

“If you’re trying to survive andyou’re trying to earn monevive a can really be a difficult situation not to have identification and to not be able to walk into an office, provide your ID, and fill out an employment form,” McDonald says.

One of the groups working to help children get identification in the state is the Texas Foster Youth Justice Project. They provide a range of free legal services including, getting a Texas identification card, original birth certificate, and Social Security card.

The group is funded, in part, by the Texas Supreme Court’s Permanent Judicial Commission for Children, Youth, & Families. Former Texas Supreme Court Justice Harriet O’Neill spearheaded the creation of the Children’s Commission in 2007 after attending a national conference a few years earlier.

“The focus [of the conference] was to try to get higher court judges to use their leadership role and trying to affect systemic change in improving the child welfare system,” O’Neill says. [That’s] “a role that judges are not really used to playing.”

When she returned to Texas, O’Neill began meeting with stakeholders throughout the state to figure out how to improve the lives of children in the foster care system. One of the needs that process identified was legal assistance, so the Children’s Commission helped fund a new group: The Texas Foster Youth Justice Project.

The director of the project is attorney Mary Christine Reed. She says since her group began, she has worked with roughly 3,000 current and former foster youth. She estimates that 10 percent of those cases have revolved around securing identification documents for these young people. Reed says some of the kids she’s worked with do not even know their legal names.

“We’ve had some clients who do not have a name on their birth certificate other than ‘infant’ and their mother’s last name,” Reed says. “We’ve had clients where their name on the birth certificate does not match what they think their name is.”

Reed helps young people who are currently, or formerly in foster care address the Catch-22 of needing identification to get identification.

Gypsy finds herself in that loop, unable to get any kind of identification. She says this leaves her unable to prove her existence.

“If I was to die today, if I was to pass away, if something happened to me, without identification, no one’s [going to] know what happened to me,” she says.

This situation is the exact one DFPS, members of the Texas Legislature and researchers and advocates are working to avoid as they tackle how to ensure children in the foster care system have access to identification.

– Joy Diaz and Becky Fogel

Tymothy Belseth’s house in Pflugerville is full of life. His home, which he shares with his wife, is a veritable Noah’s Ark with three cockatiels, two fish aquariums, two cats and one dog. Photos of the happy couple are all over the kitchen fridge, and a digital picture frame flashes photos of the family they’ve built together.

“So here are my mother and father-in-law, and that’s me [and] my wife,” Belseth says. “We’re at the Inner Space Caverns right here in Georgetown.”

What Belseth doesn’t have around the house are photos of his birth family.

“It’s hard because I have 10 siblings that I know of, and I don’t get to see [them],” Belseth says. “So, seeing my nieces and nephews [on my wife’s side] growing up – I mean, that’s about the age when the separation happened and I entered foster care.”

Belseth, now 28, met his wife when he was just 15 years old in South Texas. That happened after he had already entered the state foster care system at the age of 14.

Tymothy Belseth's first car that he saved up to buy as a teenager in foster care – It was a 1987 Camaro. (Photo courtesy of Tymothy Belseth)

Tymothy Belseth's first car that he saved up to buy as a teenager in foster care – It was a 1987 Camaro. (Photo courtesy of Tymothy Belseth)

The high school sweethearts bonded over similarities in their personalities and a love of music, especially death metal. Belseth still has the guitar he saved up for and bought when he was 17. In his living room, he pulls out the guitar’s black case that has a jagged shape. He reveals the guitar inside; it has a black satin finish.

“Made for death metal,” Belseth says.

It was music that partly motivated Belseth to find his birth certificate and Social Security card – two vital documents he didn’t have when he entered foster care. Back then, he was a long-haired teenager who needed these items to get a job and save up to buy the car that he would ultimately drive to band practice. But when Belseth approached his caseworker about getting these items, he was “told that they would get it, and they never did get it,” Belseth says.

Belseth was undeterred; he got to work getting in touch with his biological mother to get a copy of his Social Security card. And since he was born outside of Texas, he contacted his grandmother in Iowa to pick up his birth certificate at a courthouse there. That’s one of the problems people in Belseth’s situation tend to have, says the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, or DFPS. In a statement, the agency told Texas Standard that obtaining a birth certificate for foster youth is more challenging if “a youth’s birth location is unknown, [or they were] born out of state or out of country.”

It took Belseth five months to finally get both documents. When he told his caseworker, she offered to hold onto them until he turned 18. But Belseth refused. He says he “wasn’t going to give them up after it was a process to get them at 16 years old.”

These documents were a doorway to Belseth’s future. With them, he was able to apply and get the state college tuition waiver that former foster youth in Texas are entitled to; it allows them to attend state- supported colleges or universities for free. He also got his bachelor’s degree at Texas A&M University-Kingsville and his master’s degree at Texas State University in San Marcos. He eventually got a job at the DFPS – the very agency that had been responsible for him as a child.

Now, Belseth is a researcher at the Texas Institute for Child and Family Wellbeing at the University of Texas at Austin’s Steve Hicks School of Social Work. There, he develops policies aimed at improving the lives of foster youth. But proposed policies don’t get very far without backing from lawmakers, and that’s where someone like Texas state Rep. Stephanie Klick, a Fort Worth Republican, comes in.

Klick says it’s essential for kids to have their identification documents when they age out of the foster care system; without them, she says they’re left in a vulnerable position.

State Rep. Stephanie Klick is a Fort Worth Republican. (Gabriel C. Pérez)

State Rep. Stephanie Klick is a Fort Worth Republican. (Gabriel C. Pérez)

“Kids that age out of care, that do not have their identity documents, are far more likely to be homeless or victims of human trafficking,” Klick says. “If you want to get a job, even at McDonald’s, you’ve got to show ID.”

For Klick, who was first elected in 2012, improving the foster care system is a deeply personal mission.

“One thing your listeners may not know, is I actually was in foster care as a child and aged out, so I have a very keen interest in these issues,” she says.

Klick, who is the eldest of four kids, was 8 years old when she entered the foster care system. Her parents had gotten divorced and her mother struggled with mental health issues. Klick’s foster mom was a teacher at her school, and she and her family committed to caring for Klick long-term.

“They were very much interested to know what my goals in life were and how they could help me achieve those goals,” Klick says.

Part of their commitment to Klick’s future was ensuring she had the documents she needed.

“I had foster brothers and sisters that were close in age, and it was the same checklist for me as it was for them: getting your driver’s license, being able to drive, being able to get a summer job, start taking the ACT or SAT to apply for college,” Klick says.

She even graduated from high school a year early, and earned a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing at Texas Christian University.

Klick points out that one of the big differences between her experience as a foster child in the 1970s, compared to what kids experience today, is that it was easier to get identification documents back then.

“It used to be that we didn’t get our Social Security cards until we started work at a part-time summer job when we were teens. Now, kids get those almost at birth,” Klick says. “It was a lot easier to get documents then than it is today because we’re worried about identity theft.”

But there is another factor that can make it harder for foster kids to get their identification. In the DFPS statement to the Texas Standard, the agency points out that the federal Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, passed in 2004, limits the number of replacement Social Security cards an individual may receive to three per year, and ten in a lifetime. That applies to cards issued on or after Dec. 17, 2005.

DFPS wrote: “This may impact former foster youth in the future, depending on the number of times they have lost or misplaced their personal documents.”

Federal regulation aside, Klick has been working at the state level to help ensure foster youth have these documents before they age out of the system. She says one measure Texas lawmakers passed during the last legislative session in 2017 was requiring attorneys ad litem, who are court appointed advocates for minors, and the courts, themselves, to ensure that foster kids have the key three forms of identification before they age out of the system.

“It puts everybody on the hook for what kids need, not just one person,” Kilck says.

This legislative session, Klick is working on the same issue. But this time, she’s teaming up with fellow Republican state Rep. James White of Hillister. They filed HB 123, which would make it easier for kids in Texas foster care to get identification, especially when they don’t have a permanent address. White was never in the Texas foster care system, but he wants to make sure foster youth have what they need to succeed as adults. He says that’s what his parents did for him, and that’s what he wants to do for these kids.

“There’s literally nothing you can do without the appropriate identification in order to take advantage of all the great opportunities in this great state of Texas in civil life; you need an ID,” White says.

DFPS does not currently track how many kids age out of foster care without one or all of their identification documents, so it is hard to determine how many kids would benefit from this legislation. But DFPS spokesperson Patrick Crimmins says, “We are in the process of updating our Child’s Plan of Service to track if a youth received their required document[s] at age 16. This change is being made to our database – the state’s Statewide Automated Child Welfare Information System – known as IMPACT Texas.”

Belseth, who aged out of the system in 2008, says getting foster kids the right documentation matters, and that trying to estimate how many would benefit from ID legislation is beside the point.

“What matters to me is what happens to those who don’t get it. And we know, we know the outcomes are poor because their options are limited, and they can’t enter society like we all can,” Belseth says. “They don’t have the same playbook.”

–Becky Fogel

In an ideal world, children in foster care without documentation shouldn’t struggle. Lamar County Judge Bill Harris agrees.

“If somebody is having a problem, typically all we have to do – certainly all I have to do - is pick up the phone,” Harris says.

Harris has a fairly easy time getting documents for kids when they need them. That’s partly because his county has very few children in foster care – 67 by the latest count.

“I can call the local offices and the local officials and say, ‘Little Jimmy can’t get an ID card; let’s make it happen,’ and invariably we get it taken care of,” Harris says.

Judges like Harris are one line of advocates upon whom children in foster care rely. But in larger counties, that’s not always the case, often because judges in those places have higher caseloads.

Foster parents can be another key advocate for children in the foster care system who don’t have documentation.

Nikki Ladden lives in Travis County. There are numerous photos of children on her mantel.

“This was my family a year-and-a-half ago!” Ladden says chuckling.

She pulls a photo where 12 kids surround her and her husband. They’ve all been adopted from Texas foster care. But, Ladden not only cares for her own adopted children, she also still fosters others.

“This one – she’s not adopted. But oh, man, we’re hoping so! We’ve had her since birth,” Ladden says. “We are in love with this baby! But she’s also a part of this biological set right here [of] which we have adopted the older three.”

Ladden is rearing several teenagers at once. She says she has a soft spot for older children, in part, because she was an older child when she entered foster care. From that experience, she learned the importance of having all of her vital records by the time she left the system. She didn’t have any when she “aged out,” as it’s called; not even a birth certificate.

“Matter of fact, it’s been so hard for me, even to get my copy of my high school paperwork. In fact, I had to actually go down and just get another GED so I could go to college because I couldn’t even get my schoolwork,” Ladden says.

Ladden couldn’t get a job without an ID. Without a job, she couldn’t rent a place.

“So, I stayed homeless a lot,” Ladden says.

Since the time Ladden left foster care in 1982, many things have changed. Now, the Department of Family and Protective Services, or DFPS, is required to provide children with their documentation. There are also other DFPS resources that can help. But Ladden says foster parents like herself can be the child’s most effective advocate in getting those documents.

As we talk, Ladden’s youngest baby gets fussy. To calm her down, Ladden plays some classical music, and talks about another important group of advocates: caseworkers and what’s known as “attorneys ad litem” – court-appointed attorneys who represent foster children in legal matters. She says her children’s best advocate for many years was an attorney named Maya Guerra Gamble.

“She made sure they had all their paperwork, she made sure they had all their documentation. Maya is ferocious as far as making sure that things get done the way they should get done,” Ladden says.

Today Maya Guerra Gamble is a district judge. She was recently elected in Travis County and started her new job in January.

So far, we’ve learned that in order to secure a child’s documentation, the best and most effective advocates are foster parents, caseworkers court-appointed attorneys and judges. But there are some cases that require more effort and more advocates.

In a statement, DFPS told the Texas Standard that the most challenging cases are those of children born out of state who don’t have birth certificates. There are no cooperative agreements between states, and sometimes, in order to get a child’s birth certificate, a state can require a court order.

Christopher Renaud’s case was like that. He goes by CJ, and his story is a difficult one. When I sit down to learn more about Renaud’s story, he sighs, before saying, “Where do I even begin?”

He was born in Hawaii, but his parents were not married to each other. In fact, Renaud’s mother was married to another man.

“The actual husband found out about it and kind of went off on a rampage and shot my father, paralyzed him from the waist down, killed my mother instantly and then he killed himself,” Renaud says.

It was a murder-suicide. Renaud was just a few months old at the time.

Then, when Renaud was 5 years old, his dad was killed in a hit-and-run accident, leaving Renaud an orphan. After that, he went to live with family in Austin, but there, he was abused.

So, at 16, Renaud decided to start tracking down the paperwork that proved he existed. Without his biological parents, and without support from the rest of his family, Renaud turned to an organization called Partnerships for Children that works with current and former foster youth.

Erin Argue was assigned to his case.

“It took his volunteer mentor and I six months, no less than 50 phone calls to Hawaii and a senator to get this kid a copy of his birth certificate,” Argue says.

Argue says Renaud was her hardest case.

“And that was just for the birth certificate, so that we could work on the social security card, so that we could work on the ID,” she says.

They finally got the documents, and then Renaud’s wallet was stolen.

“So, in one 30-minute encounter on the street, he lost every identifying factor that he had,” Argue says.

CJ Renault and Harrison Cheung. (Photo courtesy, Harrison Chung)

CJ Renault and Harrison Cheung. (Photo courtesy, Harrison Chung)

But Argue came to the rescue. Getting Renaud’s documents the first time was so hard, she had the foresight to order duplicates for everything and put it in her office safe.

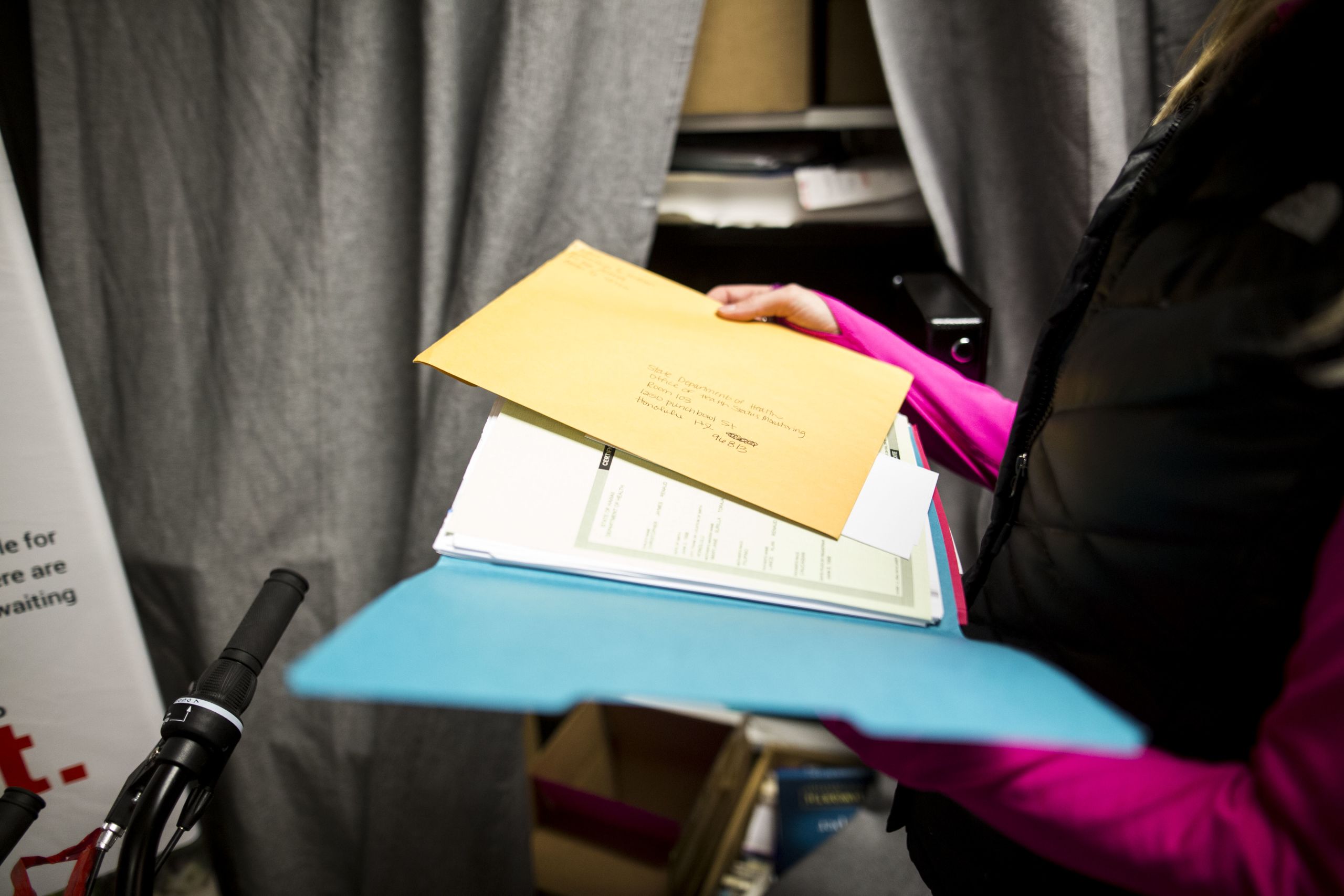

“Here it is! This is it, and we found copies of his Social Security card and his school ID,” Argue says.

Now, that safe also has identifying documents for about 100 other kids.

Erin Argue, YES Mentoring Program Coordinator at Partnerships for Children, shows the safe where she keeps spare copies of documentation for children with whom she has worked. PFC, a Central Texas nonprofit, aims to empower and support abused and neglected children in the care of Child Protective Services. (Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez)

Erin Argue, YES Mentoring Program Coordinator at Partnerships for Children, shows the safe where she keeps spare copies of documentation for children with whom she has worked. PFC, a Central Texas nonprofit, aims to empower and support abused and neglected children in the care of Child Protective Services. (Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez)

As Argue closes up the safe, a series of beeping sounds indicates that it is locked. She says it’s kind of overwhelming to think that in lieu of family or other advocates, her safe has quite literally become the most secure place for these vital records.

“It is a really powerful noise once you figure out, like, just how important stuff is in here. Because it’s not just stuff; we have, like, identity, and we have the ability to help those kiddos who don’t always have identity,” Argue says.

Because the alternative would leave these children unidentified.

–Joy Diaz

- Web Editing by Shelly Brisbin

- Multimedia by Gabriel C. Pérez and Julia Riehs

- Edited by Rachel Osier Lindley

- Copy Edited by Caroline Covington

- Scoring by Kristen Cabrera and Leah Scarpelli