Untapped:

The New West Texas

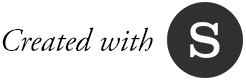

A Limited Number Of Pipelines Means It’s Hard To Get Oil And Gas Out Of The Permian Basin

There are over 440 drill rigs operating today, with no sign of a slowdown. But that also means millions of cubic feet of natural gas with nowhere to go.

A gas flare at an oil well in west Texas. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

A gas flare at an oil well in west Texas. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Originally published June 11, 2019

By Terri Langford

With so much oil production in the Permian Basin these days, there's growing pressure to find ways to get that oil out to refineries and onto tankers. Pipelines are one way, and there are several pipeline-building projects in progress.

Jennifer Hiller covers the oil and gas industry for Reuters, and says 13 pipelines are being built right now that will transport oil out of the Permian. Two big projects are the EPIC Pipeline that will run from Crane to Corpus Christi, and the Gray Oak Pipeline by Kinder Morgan and Phillips 66 that also runs eastward from the Permian Basin.

There’s also the Permian Highway natural gas pipeline that will run through the Hill Country, and some in the area are concerned.

“It has definitely run into some opposition in the Hill Country,” Hiller says.

There’s urgency for new pipelines because there’s so much oil and gas drilling going on in the Permian. Hiller says there are over 440 drill rigs operating today, and she expects the drilling to continue.

“Right now, the Permain’s making about 4.1 million barrels per day,” Hiller says. “The U.S. is the biggest oil producer, making about 12 million barrels per day.”

She says a lot of gas is also released as a byproduct of oil drilling. In fact, the Permian Basin is the second-biggest gas field in the country, Hiller says. As a result, Hiller says there are several pipeline projects in the works to specifically transport natural gas. They include the pipeline running through the Hill Country. But they’re not being built quickly enough.

“There’s a lot of effort to try to get this gas out of the Permian, but they have, basically, what analysts consider a persistent infrastructure problem,” Hiller says.

In the meantime, companies are “flaring,” or burning, the gas they can’t ship out – about 660 million cubic feet per day, she says.

That number should go down temporarily once one of the pipeline projects comes online later this year, but then flaring will increase because Hiller expects even more excess gas to be produced.

“My understanding is that that’s temporary because then you’re just gonna have more production coming online, and then we’ll have to wait for the next pipelines to be coming online in subsequent years,” Hiller says.

Written by Caroline Covington.

In West Texas, Resource-Strapped Ector County Battles Illegal Dumping

From massive scrap tire piles to raw sewage, illegal dumping is rampant in Ector County. With few resources, members of its existing environmental enforcement team are struggling to keep their heads above all of the trash.

Illegal dumping related to the oil industry is rampant in West Texas, as seen in this large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in West Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Illegal dumping related to the oil industry is rampant in West Texas, as seen in this large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in West Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Originally published June 12, 2019

By Jill Ament

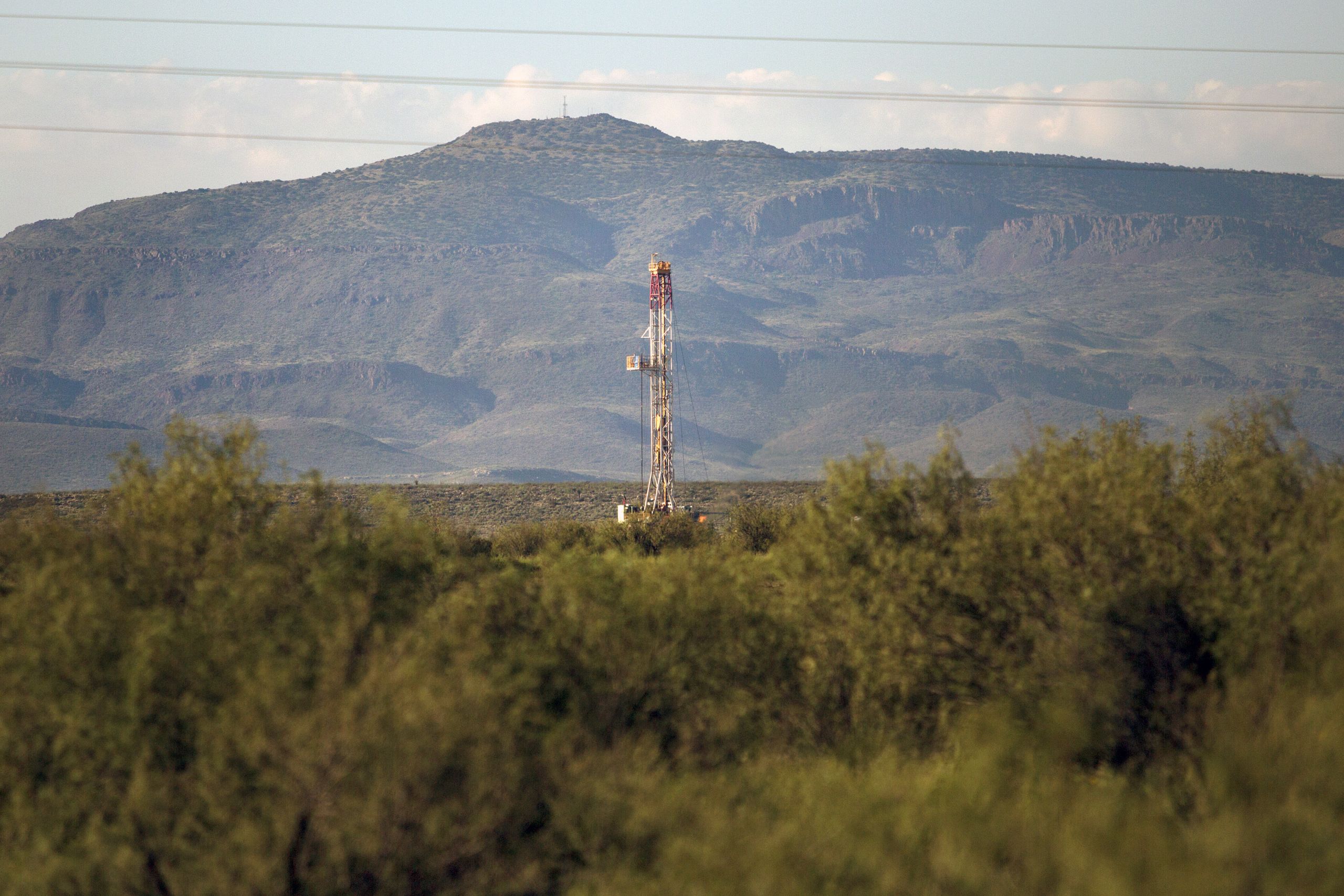

In the heart of West Texas’ oil country, illegal dumping is rampant. The problem is so bad that more counties are creating local environmental teams to combat it. For the next three days, the Texas Standard’s Jill Ament will be telling us about the scope of illegal dumping in West Texas. We begin with the leader of a tiny environmental enforcement team in giant Ector County.

Ector County Environmental Enforcement Director Rickey George steers an ATV through one unincorporated part of the county – a sort of no-man’s land called West Odessa. It’s an area bursting with oil production activity. Pumpjacks dot the dusty, flat bushland, as far as the eye can see.

“This is a road that’s obviously very popular just to dump stuff on,” George says. “We monitor this road quite frequently. Every time you see one of these oil field lease sites, you can expect trash there.”

We’ve been traveling on roads the oil companies built to give trucks quicker access to oil rigs. It’s recently rained so a lot of these roads have become mud pits.

“You got 900 square miles of county, but then you have thousands of miles of oil field lease roads,” George says.

But these oil lease roads, tucked as they are far from the main highways, attract another type of customer: Illegal trash dumpers.

Scrap tires, old oil field equipment, household appliances and furniture surround us.

A large tire pile on a residential property in west Odessa - illegal dumping related to the oil industry. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

A large tire pile on a residential property in west Odessa - illegal dumping related to the oil industry. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

To catch illegal dumpers in the act, George has hidden small game cameras along these roads. On this day, he’s keeping his eyes peeled for a man one of his cameras caught days earlier dumping cardboard boxes and plastic wrap. As we hunt for that man, another potential illegal dumper crosses our path. A pickup truck hauling old chairs, a sofa and some household appliances drives by us. George whips the ATV into a U-Turn and precedes to pull the truck over.

“Oh, yeah I don’t think so baby. He’s looking to dump that,” George says.

Under Texas law, trash over five pounds that’s illegally dumped can result in jail time. But because the person George pulls over hasn’t technically dumped anything, he’s issuing a warning.

“I’m gonna tell him tomorrow he’s gotta go to the landfill and give me a receipt that he’s legally disposed of that. If I don’t get a receipt, I issue a warrant for his arrest,” George says.

Rickey George, director of environmental enforcement with the Ector County Environmental Police. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Rickey George, director of environmental enforcement with the Ector County Environmental Police. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

George says illegal dumping in Ector County isn’t new. But with so many more people flocking to the area to get work, the area’s illegal trash problem is getting out of hand.

“So for decades, we’ve had very poor enforcement in this county on illegal dumping and that lack of enforcement has led to a major illegal dumping problem,” George says.

In an oil boom, potential new employees who flock to town, quickly test the limits of an area’s existing housing stock. George says now, more new people are moving outside of city limits either in existing RV parks, or sort of start-up RV parks that pop up randomly along county roads and on landowners’ property in West Odessa.

“One of our problem areas is people are trying to make money by providing RV housing for these people, but that requires proper septic installations, proper waste disposal, disposing of their trash. They’re all just spin offs of a population increase,” George says.

In Ector County’s unincorporated areas –the land not in a city or town –residents have to pay for private trash services that cost between $40 and $80 a month. Or, you can take a load of trash to a private landfill for about 75 bucks. George says it’s just cheaper, and easier, for residents to illegally dump.

George was born and raised in Odessa. He spent most of his law enforcement career here. So, when the county created an environmental unit to do something about all the illegal dumping going on, he signed on.

“Once I realized the scope of the problem, I do take it a little personally. I don’t like my home being trashed by anybody. Don’t mess with Texas. Don’t mess with Odessa, Texas,” he says.

George’s team mission is to enforce the state’s dumping laws, especially in oil country. Penalties can range from a small fine to months in jail.

But so far, it’s been an uphill battle.

Ector County’s population is booming because of the oil industry, but county services aren’t keeping up. Case in point? There are only three people on the Ector County Environmental Task Force: George and two investigators.

“We definitely are short-staffed. I think everybody, I think it’s regardless of what department you’re in, in Midland or Ector County, you don’t have enough people to keep up with the need,” George says.

And with an annual budget of $300,000, the team is struggling to keep their heads above, well, all of the trash.

Jesse Garcia, a criminal investigator with the Ector County Environmental Police, at a large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in west Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Jesse Garcia, a criminal investigator with the Ector County Environmental Police, at a large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in west Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Back on our ride-along, George shows me some of the most-used illegal dumping sites in the county.

We stop in front of a two-acre junk pile that includes ceiling fans, a lot of wooden crates, tires and insulation. George says people have been dumping on this particular property, without the owner’s consent, for years.

A nearby sign reads, “No Illegal Dumping.” It’s riddled with bullet holes.

Down the road, another dump site hides behind some double-wide trailers. This time, it’s an illegal scrap tire site.

At this particular spot, a man and his family were running an illegal scrap tire pile business. The offenses made by the family were jailable. George’s team was able to convict the family – but they’re currently on the run and the scrap tire pile remains.

“It’s an eyesore. It’s urban blight,” George says. “But the more pressing issue is: It’s a habitat for rodents. You just provided a motel for mosquitoes. Zika. West Nile. Disease carriers, right?”

Cleaning up an illegal dump site is expensive, especially for scrap tires. Right now, scrap tire disposal in the state of Texas runs at about $80 a ton. So, George is still trying to figure out the most cost efficient way to clean up the dump sites and keep them clean.

“Who cleans up the mess? That’s the million-dollar question in environmental enforcement,” George says. “There’s only four options: 1) he bad guy cleans up the mess. 2) The property owner cleans up the mess. 3) The taxpayers clean up the mess. 4) Or no one cleans up the mess.”

He says the sheer number of sites that need to be addressed in Ector County is overwhelming.

“I mean, just, I used to try to count them and mark them with a GPS marker… It’s just taking too much time. I don’t have time to work if I’m just marking dump sites. So, it’s just safe to say there’s thousands,” George says.

For now, when they do catch someone who’s illegally dumping, if the crime isn’t egregious and it’s a first-time offender, their enforcement approach is a bit remedial. If the offender has already dumped the trash, they’re required to pick it up and take it to the private landfill. They’ll have to give the county a receipt from the landfill the next day. Then, they’ll only have to pay a minimum fine. Otherwise, the offender will face the crimes full penalty.

“It really boils down to – local law enforcement needs to do a better job with these laws. These are laws that are traditionally ignored, and most law enforcement pawns them off to either code enforcement or it’s not my job and really it is,” George says.

Neighboring Midland County is also dealing with an illegal dumping problem. Using George’s team in Ector County as a guide, the Midland County District Attorney’s Office recently created their own environmental enforcement unit.

In the next installment of this Texas Standard series, we tell you more about the cases the DA has been prosecuting – including one involving raw sewage from a trair park ending up on a nature preserve.

Like Its Neighbors, Midland County Grapples With Illegal Dumping

An environmental enforcement team that has only been in place since October is prosecuting some serious illegal dumping cases. They’re also working with small violators to encourage them to change their behavior.

The I-20 Wildlife Preserve, an urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

The I-20 Wildlife Preserve, an urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Originally published June 13, 2019

By Jill Ament

In part 1, we told you about Ector County’s small environmental team trying to tackle a huge illegal dumping problem. Now, we take you down the road to neighboring Midland County, where they are also dealing with rampant illegal dumping. Midland County created its own environmental enforcement team less than a year ago, and they’re already prosecuting some serious illegal dumping crimes.

The I-20 Nature Preserve in Midland is a slice of wilderness, surrounded by the loud and bustling atmosphere created by the area’s current oil boom. The preserve surrounds a large, 86-acre playa lake, a key ecological feature of this part of Texas.

Kari Warden, a volunteer with the I-20 Wildlife Preserve, leads a group of children in exploration of the urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Kari Warden, a volunteer with the I-20 Wildlife Preserve, leads a group of children in exploration of the urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Elaine Magruder is the board president of the I-20 Wildlife Preserve and Jenna Welch Nature Study Center.

“Playa lakes are two to three feet deep. They’re small, round indentions in the land – where during a rain event, will fill up with water,” Magruder says.

Magruder was born and raised in Midland, Texas. She helped create the preserve back in 2007 because she wanted to protect the playa lake.

Magruder says maintaining this fragile ecosystem is especially important during an oil boom. But as industry and construction encroach the preserve, she says her mission is becoming a lot harder.

“The significance of the playa lake[s] through the High Plains and the South Plains is they’re the recharge zone for the Ogallala Aquifer, which is, you know, becoming endangered,” Magruder says. “That is where the majority of us in the Panhandle of Texas get our water.”

Late last year, a visitor was walking along the trails that wind around the playa, when they saw something peculiar. A hose was going down into the preserve and pumping something into the lake.

“On the east side of the preserve was an RV campground,” Magruder says. “It just started there in a vacant lot and they had just dug some little pits for their sewage. They had a motor and they were pumping sewage into the playa.”

An investigation by the county’s new environmental enforcement team found an illegal RV park sitting uphill from the preserve. More than 1,200 pounds of human waste was found on the property, sitting in large pits dug out of the ground. So, the RV park was shut down and its operator was arrested on felony charges. The state’s environmental agency cleaned up the pits. Meanwhile, the nature preserve teamed up with the Midland College chemistry department to test the playa’s water for any sign of harmful bacteria.

“I think we were able to nip it in the bud soon enough that there was not any damage to the wildlife or the plant life. It did not affect the water quality in the preserve so we were very fortunate,” Magruder says.

The case at the nature preserve is just one of a handful of illegal dumping crimes the county’s new environmental team has already prosecuted since it was created last October.

Tim Telck is the director.

“The regular law enforcement agencies that were handling this in the past as best as they could even then, they’re getting overwhelmed because they haven’t expanded to keep up with the population, and they’re doing their best to prioritize their calls,” Telck says.

The team consists of only three people, including Telck. And they’re tasked with enforcing illegal dumping laws for roughly 1,000 miles of county.

“We go around in the county… and it seems overwhelming,” Telck says. “It’s very daunting with everything that’s going on. And we’ve got our work cut out for us for the next few years probably.”

Cases brought up by the team are overseen by the Midland County District Attorney’s Office. Midland County DA Laura Nodolf says county commissioners acted in response to a growing number of public complaints about illegal dumping.

“Our little community was turning into a real trash source for people to dump not only household items, but for people to dump oil field-related equipment, or salt water that had been removed as part of drilling processes,” Nodolf says.

Laura Nodolf, district attorney for Midland County. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Laura Nodolf, district attorney for Midland County. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

She says when it comes to enforcing illegal dumping laws, their strategy is similar to that of neighboring Ector County. Both counties want to avoid penalizing people for small crimes. Instead, they try to work with offenders, educating them about the law and getting them to clean up their mess. They're also working with small violators to encourage them to change their behavior.=

“But when you talk about raw sewage entering the ground water and then potentially causing damage to our nature preserve, those are some of our more serious violators,” Nodolf says.

Nodolf says right now the enforcement team is in a trial period. And she agrees, they do have their work cut out for them, especially because of the area’s often shifting population.

“When you live in a town, that our population ebbs and flows based on oil, it brings in people who are not necessarily vested in the community,” Nodolf says. “We see this happen and individuals don’t necessarily care what Midland looks like. Cause they’re gonna be here for a couple of years and they’re gonna move on.”

Public complaints about illegal dumping frequently roll into the county by text and email.

Telck, the Midland County environmental enforcer, says right now the community’s biggest concerns are illegal RV parks dumping raw sewage. He says operators of illegal RV parks want to make money fast, so they avoid the three months it takes to get an operating permit.

“There’s so many people coming in and everybody has that boom/bust mentality that the oil field goes through that often times they’re gonna come in and they’re gonna try and get in and make as much money as they can before the next bust. So, they have a tendency to cut corners,” Telck says.

The operators also avoid installing a septic tank. Septic tanks are those underground sewage systems often used by homes and businesses in rural areas that are not connected to a municipal wastewater system.

The average cost to install a septic tank is around $4,000 to $5,000. But it can be three times as expensive in the Permian Basin because the soil is rockier.

“Well, that’s leading to improper septic installation which is causing leakage which is contaminating groundwater. It’s contaminating the soil. And it’s just rampant,” Telck says.

The successful prosecution of cases like the one at the I-20 Nature Preserve have county leaders and community members hopeful the team is taking the right approach.

Meanwhile, lifelong resident Elaine Magruder at the preserve says she’s learned a great deal about illegal dumping laws and just how bad the problem isgetting in the county.

“It made me aware more than anything and to act, not just to sit idly by and not do something about it,” Magruder says.

And she’s continuing her fight to maintain the playa lake, despite frequent setbacks.

“A lot of the trash ends up in the preserve in street run off when we do have rain events,” Magruder says. “For example, in a two-week period we took out 800 pounds in trash just from street runoff. This last rain event, we had a refrigerator and a mattress come in.”

An illegally-dumped refrigerator, washed in after recent rains, inside the I-20 Wildlife Preserve, an urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

An illegally-dumped refrigerator, washed in after recent rains, inside the I-20 Wildlife Preserve, an urban playa lake habitat located between I-20 and I-20 Business. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Magruder says she’s planning a roundtable this month for mainly oil workers living in hotels, RV parks and man camps. She wants to educate the area’s less-permanent population about the preserve and encourage them to come out and walk its trails.

“Once you’ve experienced being in a place like that, it makes you feel good. It makes you aware of what trash looks like in a beautiful place. And to help keep it clean,” she says.

Are Permian Basin Leaders On Their Own When It Comes To Battling The Region’s Illegal Dumping Problem?

Some environmental enforcers in the area say they have ideas on how the state could help.

A large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in west Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

A large trash pit on an abandoned residential property in west Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Originally published June 14, 2019

By Jill Ament

This past fall, Ector County voters approved a special district sales tax that would, in part, boost funding to combat the illegal dumping epidemic.

This new tax will allow more money to go into the county’s environmental enforcement team. Its director, Rickey George, will be requesting a boost in his budget for the first time in years.

“What I would want as a director is obviously more officers to do the enforcement action,” George says. “Like I said, we only have two and they cover 902 square miles of Ector County and that’s just not enough people at all. I would like to see more civilian and administration staff to help out. We need a remediation crew.”

Illegal dumping is a crime. Therefore, enforcement falls to local police. But George says there are ways the state could help counties. He says he’d like to see the state require local law enforcement officers and prosecutors to take training on enforcing the state’s illegal dumping laws.

A game camera put in place by Ector County environmental enforcement officials is used to identify illegal dumping in West Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

A game camera put in place by Ector County environmental enforcement officials is used to identify illegal dumping in West Odessa. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

“A lot of them just don’t even understand them, they don’t receive them in training,” George says. “Most prosecutors don’t get much environmental training in law school. So even if we file a case, a new prosecutor, it may be a new law to them. So, there’s a training curve, an education curve.”

He also thinks the state’s environmental agency, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality or TCEQ, could better coordinate with local law enforcement about waste illegally dumped – by businesses the agency regulates.

One of the most pressing illegal dumping issues in West Texas involves scrap tire piles.

When the area sees an oil boom, traffic on local roads and highways significantly increases. For truckers and other oil field workers mileage quickly add up the miles on their tires, so tires need replacing more frequently. George says the closest legal scrap tire processing facility is about a two-hour drive from Odessa city limits. So instead of paying for the cost of taking them to the facility, as well as the cost to process the tires, it’s cheaper for people and businesses to illegally dump them. George estimates there are hundreds of illegal scrap tire piles in Ector County. He says some of these sites have existed for years because it’s too costly for the county to clean up.

There had been a scrap tire processing facility near West Odessa, but in 2017, it was the site of a massive tire pile fire. The TCEQ had cited that facility multiple times before the fire, but George says his team couldn’t take any criminal actions against the violations. Under state law, scrap tire processors and transporters have to register through TCEQ. Then, the agency acts as a code enforcer for the businesses. Any violations made at the facility, such as having too many tires on site, or creating a fire hazard, are penalized with an administrative fine, which isn’t a criminal offense.

I requested an interview with TCEQ officials to clarify whether or not they’ve ever shut down any scrap tire businesses over serious violations. A spokeswoman declined an interview – instead saying any shutdown of a facility would have to be court ordered whether civil or criminal.

“A lot of the violations are purely administrative, which means if I saw an administrative violation, I couldn’t take any criminal action because it hasn’t been criminalized yet,” George says. “So, I would be in favor of a lot of these administrative rules being criminalized so local law enforcement in the state of Texas can use those laws.”

George has advocated for state measures that help local law enforcement keep tabs on scrap tire businesses. Two years ago, Democratic State Sen. Jose Rodriguez of El Paso filed a bill that would’ve turned certain code violations made by scrap tire businesses into criminal offenses.

Here’s Sen. Rodriguez in 2017:

“The problem is that there is not enough enforcement authority… and that’s what this bill tried to provide. This issue is not viewed as a high priority for a lot of people and then people are just getting away with dumping scrap tires all over the place.”

Rodriguez’ measure included ways to better track those transporting scrap tires. His bill required TCEQ to provide stickers to vehicles registered through the agency as legal scrap tire transporters. Rodriguez says this would’ve helped local law enforcement catch those who were illegally hauling scrap tires.

“The idea behind the bill to promote health and safety, we’re going to require retailers to provide more information as to what happens to these scrap tires when they are brought into the store,” Rodriguez says. “That they be secured so that nobody can be taking them illegally and dumping them, that the people who are going to be removing the tires from the retailers or processing plants are registered transporters.”

Under Rodriguez’ proposed measure, scrap tire facilities and haulers who racked up repeat offenses could be fined up to $25,000. The fines would have been applied to the costs of cleaning up and closing illegal scrap tire businesses or dump sites.

Rodriguez says several law enforcement agencies, tire businesses and recycling centers and health officials were involved with drafting the proposal. The proposal was passed by the legislature, but vetoed by Gov. Greg Abbott.

“His reasoning was apparently it was too much regulation. I am personally baffled by the governor’s reasoning because it’s not providing more regulation than what’s already in the books,” Rodriguez says.

In his veto, Abbott said Rodriguez was creating a new and vaguely-defined crime, and thought there were better ways to address the problem.

This year, Rodriguez proposed more watered-down version of the same bill. It cleared the Senate and a House committee, but lawmakers didn’t get to it on the House floor before deadline.

Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Meanwhile in West Texas, Ector County’s Rickey George would like to bring some of his ideas to the table for his own state lawmakers. He admits he has yet to propose a plan to anyone. And Ector and Midland County’s state senator, Republican Kel Seliger, says he wasn’t aware of any new problems with illegal dumping, like issues with raw sewage or illegal scrap tire piles getting out of control. So he didn’t propose any legislation in the 2019 session.

“I don’t know that they needed our help with anything… I’m not aware specifically of the types of waste you’re talking about,” Seliger says. “If there’s a particular or new problem in Ector County, if there’s something that needs to be done in law – we’ll do it.”

So for now, counties in the Permian Basin will bear the brunt of taking care of their illegal dumping problems.

“We take a lot of pride in the fact where we started, where we came, and where we’re going with it. And hopefully we can reverse the trend of illegal dumping and kind of set the tone of Ector County and Odessa, West Texas in general,” George says.

The environmental enforcement teams in Ector and Midland counties are working to create a regional illegal dumping task force. That’s because they say neighboring counties that are smaller, and even less equipped, are overwhelmed by illegal dumping, too.

Booms And Busts Have Defined Midland’s History, But Is It Time To Stop Using Those Terms?

“We’re not going to talk like that. We’re going to talk about sustainability, talk about the long-term future.”

Both Midland and Odessa saw a boom to their population numbers in 2018, according to new data released from the U.S. Census. (flickr.com/photos/pkmonaghan / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Both Midland and Odessa saw a boom to their population numbers in 2018, according to new data released from the U.S. Census. (flickr.com/photos/pkmonaghan / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Originally published June 5, 2019

By Mitch Borden, Marfa Public Radio

The Permian Basin has never been busier. More oil is being pumped than ever before, thanks to hydraulic fracking. And energy companies are making plans to stick around long-term. By most accounts, the region is booming. But, some analysts and community leaders believe the oil industry is entering into a more stable phase where the days of crazy booms and terrible busts may be a thing of the past.

And there’s no place better to find out whether this is true than Midland, Texas. The city has been the corporate center of the Permian Basin’s oil industry for almost 100 years. This also means the oil and gas industry’s notorious boom-bust cycle is practically baked into the community’s DNA

That’s why it was so surprising to hear that Midland’s mayor Jerry Morales had said booms may be a thing of the past. He says Midland’s changing and he wants people to know that.

“We’re rebranding Midland. We are not a man camp. We are not just someplace to get a job,” Morales says.

Morales sees the oil industry as a stabilizing economic force that could put Midland on the path to sustained growth. That’s a hard sell to residents and investors – if everyone believes the economy could fall out from underneath them when the next bust hits. So he doesn’t want to use the terms “boom” or “bust” to describe the region’s economy anymore.

“We’re not going to talk like that," Morales says. "We’re going to talk about sustainability, talk about the long-term future.”

Pump jacks are a common site all over the Permian Basin as the region’s current up swing continues. Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Pump jacks are a common site all over the Permian Basin as the region’s current up swing continues. Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Morales does have reasons to be optimistic. Over the last ten years, the West Texas oil industry has been exploding. By combining hydraulic fracking and horizontal drilling oil, a process using water, chemicals and sand to extract oil from shale formations, companies have unlocked vast new reservoirs of oil and natural gas in the Permian Basin. This process is also cheap and really efficient so it’s easier for producers to make money even if the price of oil suddenly drops.

“So, we’ve seen the boom-bust cycles [in the past.] We’ve seen the economy go up and down. What’s changed is we’re more sustainable,” Morales says.

Midland’s past experience with devastating oil busts is a tough memory to let go of. To understand this, we need to go back in time about 40 years.

The price of oil was really high in the early 80s. At its peak, a barrel went for over $100, in today’s money. So, West Texans were getting rich. Stories of Midland at this time included tales of lavish mansions, crazy parties, expensive cars, and private planes.

But then suddenly in 1986 the oil market tanked.

In West Texas, the price of oil fell by about 50% in six months. The main cause of the crash was an oil glut, and Saudi Arabia, and other OPEC countries flooding the market with cheap oil. This caused oil prices to free fall, and turned Midland’s boom into a cataclysmic bust.

Businesses closed, Home-for-sale signs popped up everywhere, and a lot of residents left town. There is still evidence of the crash in Midland today. In downtown, there are skyscrapers that have sat empty for decades because of the 1986 bust, reminding residents of the kind of damage a downturn can leave in its wake. On the other hand, there are also huge construction projects currently going on in Midland that send the message: oil is back and stronger than ever.

The Vaughn Building in downtown Midland has largely sat empty for the last three decades. Carlos Morales / Marfa Public Radio

The Vaughn Building in downtown Midland has largely sat empty for the last three decades. Carlos Morales / Marfa Public Radio

According to Midland’s Mayor Jerry Morales, the Permian Basin’s economy is nothing like what it used to be.

“Oil and gas may drop. We saw that in 2015 when it hit $30, but you know what happened? Everybody stayed,” Morales says.

Morales says that during the oil price drop that hit about three years ago businesses didn’t shut down as they would have in the past. There also wasn’t a major population drop. Instead, people stuck around to weather the downturn. In fact, Midland is the fastest growing community in America, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Another reason the Permian Basin is becoming more resilient is that there’s a huge demand for its oil overseas. Before 2015, the U.S. banned exporting the majority of its oil, but now that ban has been lifted, opening up the world to Permian oil producers. Many think this is a good thing that will make the American oil industry more secure.

Trey Murphy, a geographer who studies the effects of the energy industry on communities, doesn’t see it that way.

“It only takes one tweet or it only takes one gunshot in the Middle East to drastically change the price of oil,” Murphy says.

Murphy believes no matter what anyone says, Midland is still in a boom. The city has all the classic symptoms – rapid economic growth and strained infrastructure, along with labor and housing shortages.

He says the sunny outlook on the oil industry’s future is pretty common.

“Everything looks great when you’re in the middle of a boom, but a bust really isn’t that far away,” Murphy says.

That’s hard for some to imagine, when major oil companies like Chevron and ExxonMobil are snatching up land in the Permian Basin. The growing presence of the majors really only started recently and their continued investment in the region is reassuring to those who believe the West Texas oilfields are stabilizing.

People shouldn’t get too comfortable though, says historian Diana Davids Hinton, who lives in Midland and studies the Permian Basin oil industry.

“There’s no such thing as a sure thing, economically, in an environment like this,” Davids Hinton says.

She agrees that the low cost of fracking somewhat shields the industry from dramatic market swings.

But “things only stay booming while people are making money. And that’s something the industry can’t control,” she says.

No matter what companies do to try and influence the price of oil, only the global market sets the price. That means the price of oil could go down, or up, for any number of reasons – like if there was an oil glut, new restrictive legislation, or something totally unexpected happens — like in 1986.

According to Davids Hinton, this means booms vary. They can go for weeks, months, years or longer.

In the end, though, she says, “It’s impossible to say how long one is going to last.”

Right now, it does look like oil companies are set up to have a long run in the Permian Basin. Davids Hinton doesn’t dispute this, but she says just because a large bust hasn’t hit the region recently doesn’t mean one isn’t right around the corner.

'Carbon Neutral Oil' Is Promising, But Far From Guaranteed

Some experts say sequestered CO2, even if it’s used for oil production, can help the planet in the short-term. But critics say it prolongs the use of fossil fuels.

Oil and gas development seen in the West Texas Permian Basin. Photo by Bruce Gordon via Flickr

Oil and gas development seen in the West Texas Permian Basin. Photo by Bruce Gordon via Flickr

Originally Published June 20, 2019

By Travis Bubenik, Houston Public Radio

Scientists say technology that keeps harmful levels of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, even sucking it out of the air, will be an essential tool in the fight against climate change. But who’s going to pay for it?

Ironically, the answer could increasingly be: oil companies. They see “carbon capture” as a way to make money. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a sure-fire way to save the planet.

The prospect of “carbon-neutral oil” is promising, but it’s tricky.

Fossil fuels contribute to climate change, but oil and gas companies are increasingly billing themselves as part of the solution as well. They talk openly about the “energy transition” to cleaner sources like wind and solar. The biggest oil producer in the West Texas Permian Basin, Occidental Petroleum, has even talked about someday becoming “carbon neutral.”

Oxy executive Charlene Olivia Russell outlined the company’s carbon philosophy at a recent panel discussion in downtown Houston hosted by the Center for Houston’s Future.

“We have a team called Oxy Low-Carbon Ventures now that is solely focused on this activity,” she says. “We believe that many technologies are needed for the world to use to reduce the carbon emissions needed to reach our climate reduction goals.”

Occidental is planning a massive West Texas facility that would suck carbon dioxide from the air and pump it underground. The carbon, once underground, where it’s meant to stay forever, is used to loosen up oil that might otherwise be too hard to get to. So the company’s project would lead to more oil production.

Some environmental groups say there is a net climate benefit from these kinds of projects.

“This is a way that we can almost immediately begin putting away, initially, tens of millions of tons a year of CO2, and as time goes on, ramp that up,” says Scott Anderson with the Environmental Defense Fund.

But here’s the thing about offsetting the carbon footprint of a barrel of oil: it doesn’t necessarily work forever.

“The carbon balance of the operation varies significantly through time,” says Vanessa Nuñez-López, a researcher with the University of Texas’ Gulf Coast Carbon Center who has studied this extensively.

Her research shows the process, called “enhanced oil recovery,” does work initially.

“For the first several years of operation, all EOR projects produce net carbon negative oil. Meaning that more carbon is stored, than is emitted,” Nuñez-López says.

But, as time goes on, less carbon gets pumped into the ground, while the oil continues coming out. In other words, you don’t need as much carbon to get the oil after those first several years.

So, as Nuñez-López explains it, eventually the whole “carbon balance” can start to flip.

“The operation transitions from operating under a negative carbon footprint, to operating under a positive carbon footprint,” she says.

But to be clear, Nuñez-López still thinks this technology is a good thing for the planet. She and other experts say the world is going to need fossil fuels for a while, so you might as well chip away at the climate impact in the meantime.

“Time is of the essence,” says Anderson. He argues there’s an urgent need to pump more carbon into the ground.

“We can make sequestration in oil fields happen now, so we ought to do it,” he says.

Still, critics say this all just prolongs the use of fossil fuels. Some environmental groups have opposed tax credits meant to encourage new oilfield carbon capture, while others take a more nuanced view about the oil industry’s role in fighting climate change.

“Those companies have a responsibility to get us out of this climate mess,” says Adrian Shelley with the advocacy group Public Citizen. “They’re the ones who got us into it.”

Shelley said while he believes there is a benefit to using carbon for oil, his group does not support the idea when the carbon comes from coal plants, as those projects could prolong the life of the coal industry.

Even backers caution this kind of climate solution will only work alongside many other approaches to reducing emissions. And the research suggests it has to be carefully monitored through time to maintain the benefits.

Wind Farms Invade Remote Devils River

Turbines bring clean energy, but they’ve fundamentally changed people’s view of this pristine corner of West Texas.

Devils River. Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Devils River. Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Originally published July 3, 2019

By Michael Marks

Shady spots are few and far between in the Devils River State Natural Area, but if anyone can find them, it’s Joe Joplin. He’s superintendent of the area – 37,000 acres of untamed Texas halfway between San Antonio and the Big Bend.

Joplin has found a respite from the 100-degree heat under a limestone ledge overlooking the Devils River. It’s one of the most remote and pristine bodies of water in the state – a clear, spring-fed stream that never passes through a major city. From Joplin’s current spot, the closest town is Del Rio, over 60 miles away.

“You’re looking on bluffs and horizons for miles and miles and miles,” Joplin says. “And what do you see? You don’t see anything manmade.”

But climb out of the river valley and onto the mesas that surround it, and modern life comes back into view: wind turbines – 69 of them, spinning mechanically on the horizon. They came online in 2017, to the chagrin of locals like Joplin.

“What you feel is another part of wild Texas is kind of gone a little bit. You wonder what it will look like in the future,” he says. “Are there going be locations you can look around and not see development?”

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

It’s a question that many who live near the Devils River now wonder. It’s the kind of place you go to in order to find wildness and isolation. But through the wind farm, the modern world has come to southwest Texas.

A different place

The wind farm is operated by Akuo, a French energy company. Brazos Highland Properties, a Chinese company, owns the land. Walmart and another multinational corporation buy the 150 megawatts of power it generates. But that might be just the tip of the iceberg. Since the current wind farm was erected, Brazos Highland Properties has become the largest landowner in Val Verde County. The company owns over 140,000 acres in the area, with plans to install over one hundred more turbines.

For longtime residents like Dell Dickinson, that would be a catastrophe. Dickinson grew up near the Devils River. He’s 75 now, and lives by himself on a 7,000 acre ranch in the area that’s been in his family since his grandfather bought it in 1942.

“Back in those days, one could look 360 degrees around the horizon and see no lights whatsoever. The only lights you ever saw at night were the natural stars and the moon,” Dickinson says.

Dickinson’s back porch boasts a stunning view of his property: seemingly endless acres of steep-sloped mesas, early summer sotol stems waving lazily in the breeze. But if you squint, you can just make out the wind turbines in the distance. They’re 18 miles away from Dickinson’s house. And the darker it gets, the clearer they become.

“What I’ve learned to do is just not look in that direction. Because literally every time I see those lights, I get angry,” he sys.

Each turbine is topped with a red light to warn planes of their presence. Now, every night – the entire night – bright red beams crash through the darkness in single-second intervals as the lights flick on and off. This, in a place known for some of the darkest skies in the world. Dickinson still remembers the first time he saw them.

“I remember I was in the house and I was coming back here just to sit out on the deck and enjoy the evening. And I mean I literally opened the door and I think my jaw just dropped. That thing looked like an extraterrestrial landing strip to me,” he says.

“We don’t have the authority to do that”

In a state that’s increasingly urban, residents and visitors alike value the Devils River for its isolation and wildness. If those qualities disappear, people like Dickinson wonder what’s left. It is a classic case of locals demanding “not in my backyard.” They’re not opposed to wind energy in principle, but they are opposed to generating it in Val Verde County.

“Why deliberately ruin a pristine area when there are all these other places that are already so damaged that it wouldn’t hurt to put it on there?” Dickinson says.

An advocacy group called the Devils River Conservancy has launched a campaign against the wind farm’s expansion, and lobbied the legislature to limit development. They’ve drummed up plenty of attention, but the turbines would be on private land, out of local government’s reach.

“Do we have the authority to say ‘no, don’t put it there?’ No, we don’t have the authority to do that,” says Lewis Owens, the Val Verde County Judge.

Owens has met with representatives from Brazos Highland Properties, and he says they’re open to working with the community. But ultimately, there’s little he or anyone else could do to prevent them from putting up more wind turbines on the property.

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

If the expansion could be curbed, it would be because of nearby Laughlin Air Force Base. It’s the largest training base in the country -- a major revenue stream for Val Verde County communities -- and if it’s determined that the turbines may interfere with tis flights, that could hold up the future development. Owens said the future turbines’ effect on the base’s flight patterns is the county’s “biggest concern.”

But it’s unclear if, much less when, the Department of Defense would order any changes to Brazos Highland Properties’ plans. That has Dell Dickinson thinking about what comes next. He’d always thought he’d keep the ranch in his family, but if more turbines go up, Dickinson may be surrounded by them, and they’d likely be closer to his home than the current group.

“I think at that point I could no longer live out here,” he says. “It’s no longer what I loved.”

Kermit's Fortune Is Made Of Sand

Once a playground for the area's residents, the town's sand dunes are in demand by oil companies that use the sand for hydrolic fracturing.

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Photo by Michael Marks/Texas Standard

Originally published July 5, 2019

By Michael Marks

In the late 1840s, the U.S. government commissioned a series of maps to help guide those who were lured west by the California Gold Rush. One of the new charts showed an area to avoid, about 60 miles west of Midland, near the present-day town of Kermit: a long, unforgiving band of sand dunes. These days, the spot is still of interest to fortune seekers – although they’re not avoiding it anymore.

Sand is just a part of life in Kermit. It fills the treads of your shoes, collects next to curbs, and when the wind kicks up – which it often does – you can feel small stings as invisible grains whip across your face. Drive ten miles out of town on Highway 115, and you will find their source: over 1,200 acres of sand dunes, a veritable Sahara in miniature. They’ve been around for about 12,000 years, and for most of that time, no one’s had any use for them. With one exception. For generations, riders brought their dirt bikes,

“We lived at the sand hills. I mean we *lived at the sand hills,” says Chris Martinez.

She grew up in Kermit. Now she’s president of the chamber of commerce. She says the dunes were a longtime gathering point for the community.

“We always had quad runners and dirt bikes and, you know, you could go down the street and more than likely everybody had a quadrunner, a dune buggy, a whatever, they always had them,” Martinez says.

And it wasn’t just for riding. The dunes were where you went to watch Fourth of July fireworks, to hunt for Easter eggs, to party after your high school graduation. But these days, you don’t see any families or joy riders heading to the hills. Instead, it’s a constant stream of trucks, hauling off the sand dunes one load at a time. This resource that was once fairly useless has become a hot commodity. The sand is used for hydraulic fracturing, a method of oil and gas production better known as fracking. Drillers shoot it underground to keep fractures they make in the rocks open. As oil and gas development has exploded in West Texas, so too has the demand for sand. So, if you’re like Tony Underwood, and happened to own over 1,000 acres of the stuff, you were in luck.

“You know the sand hills was one of those deals, it wasn’t for sale. These people approached us,” Underwood says.

Underwood and his brother used to own the dunes. They grew up in Kermit, so when they had the opportunity to buy the property from Winkler County, they jumped on it. It was a good business for them, charging folks $10 a head to get in and ride. They’d invested over $1 million into the business, including putting in a dance hall. But in 2017, a sand mining company from Houston, called Hi Crush, made them an offer for the dunes. He says they had no plans to sell.

“But when people come to you and you tell them they can’t afford it, and then they show you they can, what do you do?” Underwood says.

He and his brother sold the property for an undisclosed but apparently handsome price – when we spoke, Underwood was at a ranch he bought in 2017 from Walmart heiress Alice Walton. The sale of the dunes made quite a few people upset.

“To me, personally, it was heartbreaking,” Martinez says. “The kids that are growing up after the fact, they’re not going to have any idea how much fun the sand hills were.”

Kermit has seen booms and busts before, but since its sand has become a valuable commodity, it’s been transformed. Jerry Phillips is the mayor.

“Well back in the slowdown, when oil was nine, ten dollars a barrel, you could probably shoot a rifle down the main street of town and not worry about hitting anyone,” Phillips says.

But those days are gone. The 2010 census put Kermit’s population at just over 5,000 people. But according to recent surveys, the real figure is more than double that. That means finding housing is difficult, and if you do, it’s expensive. Over 100 RV parks have popped up in the city limits, mostly filled with oil field workers. There’s constant truck traffic, damaging roads faster than the city and county can repair them. The traffic light at one of the main intersections has been damaged so many times, that the city has left it as a blinking red light. Most businesses in town are hiring, but few can match what the oil field pays.

“What we’re trying to do is accommodate what the growth is bringing to us, and trying to make it a better place to live,” Phillips says.

It’s certainly a more prosperous place to live, at least for some. Shops and restaurants are all packed, and there’s new development coming too: a couple hotels, an O’Reilly Auto Parts store and a McDonald’s. It’s busy and loud, and while Chris Martinez wishes she had the sand hills back, she also likes all the new money coming in.

“I like the fact that our town is growing, I like that. I know I could live anywhere, but this is my town,” Martinez says.

It’s both the same place that she grew up, and completely different. The sand – the sand that seems to be everywhere, all the time – reminds her of both.

New Pipelines To The Permian Basin Are Projected To Double The Oil The Region Can Pump Out

“You could see a fair amount of congestion getting that crude on the water because pipelines are turning on before a lot of that export infrastructure is going to be in place.”

Pipelines are being laid all across West Texas as the Permian’s oil boom continues. Four manger pipeline projects are set to come online in the next two years.

Pipelines are being laid all across West Texas as the Permian’s oil boom continues. Four manger pipeline projects are set to come online in the next two years.

Originally published July 9, 2019

By Mitch Borden, Marfa Public Radio

Four major oil pipeline projects are set to connect West Texas to the rest of the market in the next two years. John Coleman is with research firm Woods Mackenzie. He explained these new pipelines will lead to an excess of open space.

“Within the next two years from now, you’re going to have nearly 3.5 million barrels a day of capacity come online in that time. For reference, you’re literally doubling the [Permian Basin’s] pipeline capacity in two years.”

Coleman says once that happens, it will take some time before producers can drill enough oil to fill all of the pipelines, which will give the region’s price per barrel a temporary boost. Three of the four pipelines coming online in the next few years should be operating around the beginning of 2020.

Even with this added infrastructure, the oil industry may still have to deal with some bottlenecks. The three pipelines that are about to be completed in the next year are all headed to Corpus Christi, where the oil will mostly be shipped overseas. Additional storage and shipping facilities are still being developed there though. So, according to Coleman:

“You could see a fair amount of congestion getting that crude on the water because pipelines are turning on before a lot of that export infrastructure is going to be in place.”

Coleman says these downstream issues will eventually be dealt with and the new pipelines should allow growth to continue in the Permian without the fear of backups hanging over the region — at least for the near future.

Worker Shortages In The Permian Basin Continue Even As Companies Tap The Brakes

“People think strictly money and they get out there and it’s a sacrifice and it’s a hard job. It’s a hard life.”

Workers drain and clean trucks for 12 hours a day for three-week shifts at Milestone Environmental Service’s Orla slurry disposal site. Photo by Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Workers drain and clean trucks for 12 hours a day for three-week shifts at Milestone Environmental Service’s Orla slurry disposal site. Photo by Mitch Borden / Marfa Public Radio

Originally published July 11, 2019

By Mitch Borden, Marfa Public Radio

The Permian Basin’s oil industry hit its first real slow down in years over the last seven months. Companies have cut thousands of jobs and the number of oil rigs has fallen. But at the same time, the region is producing more oil than ever and labor shortages are running rampant.

Even though the oil industry is becoming more efficient, labor shortages aren’t expected to go away. In fact, they may get worse in the coming years. This becomes clear when you visit some of the oil industry’s rural outposts.

Take the small town of Orla, Texas, for example. It sits just south of the Texas-New Mexico border. The town of just a handful of residents is basically a four-way stop. It’s constantly filled with large herds of semi-trucks, some of which are filled with water and mud from drilling operations. Some of them are headed to a waste disposal site just outside of town run by Milestone Environmental Services.

There, workers quickly unscrew caps, releasing black fluid from the truck’s huge tanks. The dark liquid runs into nearby drains, as site manager Julio Ibarra looks on.

After the tanks are emptied, Ibarra explained, his crew will get high-pressure hoses to start cleaning the truck. In a day, they’ll service roughly 100 trucks.

It’s dirty work and things get hot under the West Texas sun, but Ibarra loves his job.

“I mean to get to the nitty-gritty,” Ibarra says. “The pay’s great, the housing. All they’re asking is for a full day’s work.”

The Permian Basin’s oil industry has been going through a slight cooling period since the beginning of the year. The area’s rig count dropped by 32% from January to May, according to the Dallas Federal Reserve, and companies related to the oil fields have cut thousands of jobs over the last six months. But you wouldn’t know this is happening by driving around. The roads are packed with workers like Ibarra, there are 18-wheelers everywhere and there’s drilling happening practically everywhere you look.

The ability of this West Texas industry to continue growing amid national job cuts is special, especially since this hasn’t been the trend in oil patches across America. In the last 5 years, the nation has lost about 41,000 oil and gas jobs according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Meanwhile, the Permian is producing around 4 million barrels of oil a day — which is a new high — and in 2018 the region added around 10,000 jobs related to the oil industry.

Jesse Thompson is a senior business economist at the Dallas Federal Reserve and explains West Texas may have a lot of oil, but it doesn’t have enough people to work in it.

“Everybody to the extent necessary is bringing their labor in from outside the region,” Thompson says.

Thompson also explained it now takes fewer workers to produce a barrel of oil than it used to because of improvements in technology. He also pointed out that the Permian Basin’s major growth hasn’t prevented labor shortages from happening — at least not yet. Even though some in the West Texas energy sector have been reducing their workforce recently, that number is nowhere near the amount the industry’s added in recent years — and many more jobs still need to be filled.

“I don’t think I’ve talked to a single person from an industry that hasn’t worried about labor shortages in the recent past and labor shortages going forward,” Thompson says.

Companies, especially those related to oil, offer as many perks as they can to lure potential employees – things like health, dental and eye insurance. There’s also housing options, retirement plans, competitive pay with overtime, and per diem.

“If you need a worker, if you need a skill set and it’s not available, you do what you need to do to get them in there,” Thompson says.

That means companies fly people in, recruit anyone they can, poach workers, and do whatever it takes to keep employees.

At recruiting fairs, like the one where Jason Wiggins was looking for applicants, companies in the energy sector are trying to attract applicants.

Wiggins manages service crews across the Permian Basin for SPN Well Services, an oil field service company that helps with drilling and production across the United States. “You get five or six guys, you lose two or three,” Thompson says.

He’s lived and worked in the Permian Basin since 2012 and he’s never seen it so busy, which makes it particularly challenging to retain workers.

“I would say we’re usually looking for at least 15 to 20 guys,” Wiggins says.

Many workers jump from job to job looking for the company with the best pay or benefits. But for Wiggins, his challenge when hiring isn’t finding applicants — its finding skilled workers.

They’re a hot commodity because every downturn in the oil market means a slew of workers exit the industry for good to pursue new careers, which leaves businesses adrift. Companies are burdened with having to find and train a new generation of workers.

Wiggins thinks many get into the oil business for the good wages without thinking about the price they’ll have to pay.

“People think strictly money and they get out there and it’s a sacrifice and it’s a hard job. It’s a hard life,” he says.

Standing outside a gas station in Orla, Rodrigo Burciaga agrees. “I mean it sucks, it’s all about the money out here.”

He dropped out of college after getting married. He supervises construction crews for a water transfer company and is currently making around $80,000 — lower than what he’d like to be making. Burciaga says there is no love lost between companies and their employees. Every worker is here to make money, he said, so if you’re out in the field and a company sees that you’re a good worker and offers you better pay, you take it.

“So everyone is constantly changing,” says Burciaga.

He doesn’t expect to stay in the oil industry forever. He’s going to get his degree and become a graphic designer. But he also says he’s going to ride the oil wave for as long as he can. And analysts believe that could be for years.

With new oil pipelines coming online soon, the region is preparing for even more growth. That means the Permian Basin’s labor problem isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

One Company Wants To Use Hydrogen For More Than Rocket Fuel And Fertilizer

Equinor, a Norwegian company, wants to use hydrogen in homes and power plants.

HydroStatoilraffinaderiet inKalundborg, Denmark. Photo by Lcl / Public domain

HydroStatoilraffinaderiet inKalundborg, Denmark. Photo by Lcl / Public domain

Originally published July 16, 2019

By Kristen Cabrera

Norwegian company Equinor wants hydrogen to be the energy source of the future: one that heats homes and powers factories. While hydrogen isn’t yet widely used for those purposes, it is a viable option, especially for energy companies looking to reduce carbon emissions. That’s because hydrogen can be made from natural gas – something Equinor has a lot of.

The Houston Chronicle’s James Osborne says the world is heading towards a low-carbon-use future.

“The world is going to be low carbon, which everything looks that way right now,” Osborne says. “This is potentially a good business opportunity for them.”

Osborne says European energy companies are often known for being more forward thinking.

“They’re sort of on a faster timeline than some of the oil companies here like Exxon or Chevron,” Osborne says.

But American companies aren’t far behind; they’re investing development of low-carbon energy sources, too.

“They, in their own right, are busily trying to find their own way through this low-carbon world,” Osborne says.

A major hurdle for energy companies is figuring out how to produce low-carbon fuel on a large scale. Hydrogen, for example, is highly flammable.

“If they can figure out the technology, whether it’s from NASA or something else, they can have a huge role to play in the energy system of the future even if oil and natural gas are playing a diminished role,” Osborne says.

Written by Geronimo Perez.

In The Permian, An Oil Boom's Hidden Challenges

West Texas wells produce more oil than the domestic market wants. But all that oil has to go somewhere.

Flickr/Richard Masoner (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Flickr/Richard Masoner (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Originally published August 13, 2019

By Michael Marks

Because of advances in technology, extracting oil and gas is cheaper and easier than ever. Each day, in the Permian Basin alone, producers will pump roughly 4 million barrels of oil out of the ground. It's projected that average production will go up by 1 million barrels per day each year for the next four years. The amount of oil being produced is more than the domestic market can use, forcing the industry to find other places to sell it.

Dr. Ramanan Krishnamoorti is the chief energy officer at the University of Houston, and recently cowrote a Forbes article on the ongoing oil production boom. When the Permian Basin became the center of an oil boom, it was shareholders and investors who made sure the business continued to grow to its current rate, despite the fact that demand didn't warrant that much production.

“It’s all about return on investment. There’s been significant capital put into the Permian,” Krishnamoorti says. “And it’s now time to try and get back value on that capital that’s been put in.”

As oil and gas refineries and extraction sites across the world are reaching retirement age, and production is declining, the Permian Basin provides an excellent opportunity, Krishnamoorti says. The world is looking for a new source of oil and gas, and the Permian Basin is the perfect place is find it.

“The world is hungry. The world is in a delicate balance with supply and demand with oil and gas,” Krishnamoorti says. “The Permian is the perfect place to produce that new supply for the world as we look at the global situation, not just the U.S.”

An oil boom presents problems. Once oil and gas is out of the ground, producers need to find pipelines, storage and transportation to accommodate crude oil. A pipeline that will connect the Permian to Corpus Christi aims to at least partially solve the problem, but the project would need to accommodate 4 million barrels of oil a day in the next three years.

“When you try to go through that kind of expansion, there are challenges –massive challenges, with people with skills, with capital,” Krishnamoorti says. “It’s going to be a tightrope finish to see if we can get that kind of export capacity ready in three years.”

Despite the growing use of renewable energy sources, Krishnamoorti says that in the coming years, the global demand for oil will between 70 million to 120 million barrels per day. Current demand is about 95 million barrels per day. Most increased demand comes from foreign markets.

“For the past 20 years or so, we have been using more oil than we’ve found. Clearly there is going to be a need for this oil,” Krishnamoorti says. “There’s going to be a demand that is significant because of the demand from growing marketplaces in Asia, Africa and beyond.”

Written by Marina Marquez.

How The Use Of Satellites Has Started A ‘Space Race’ In The Permian Basin

Oil industry companies are using satellites to track competitors and find leads for new business.

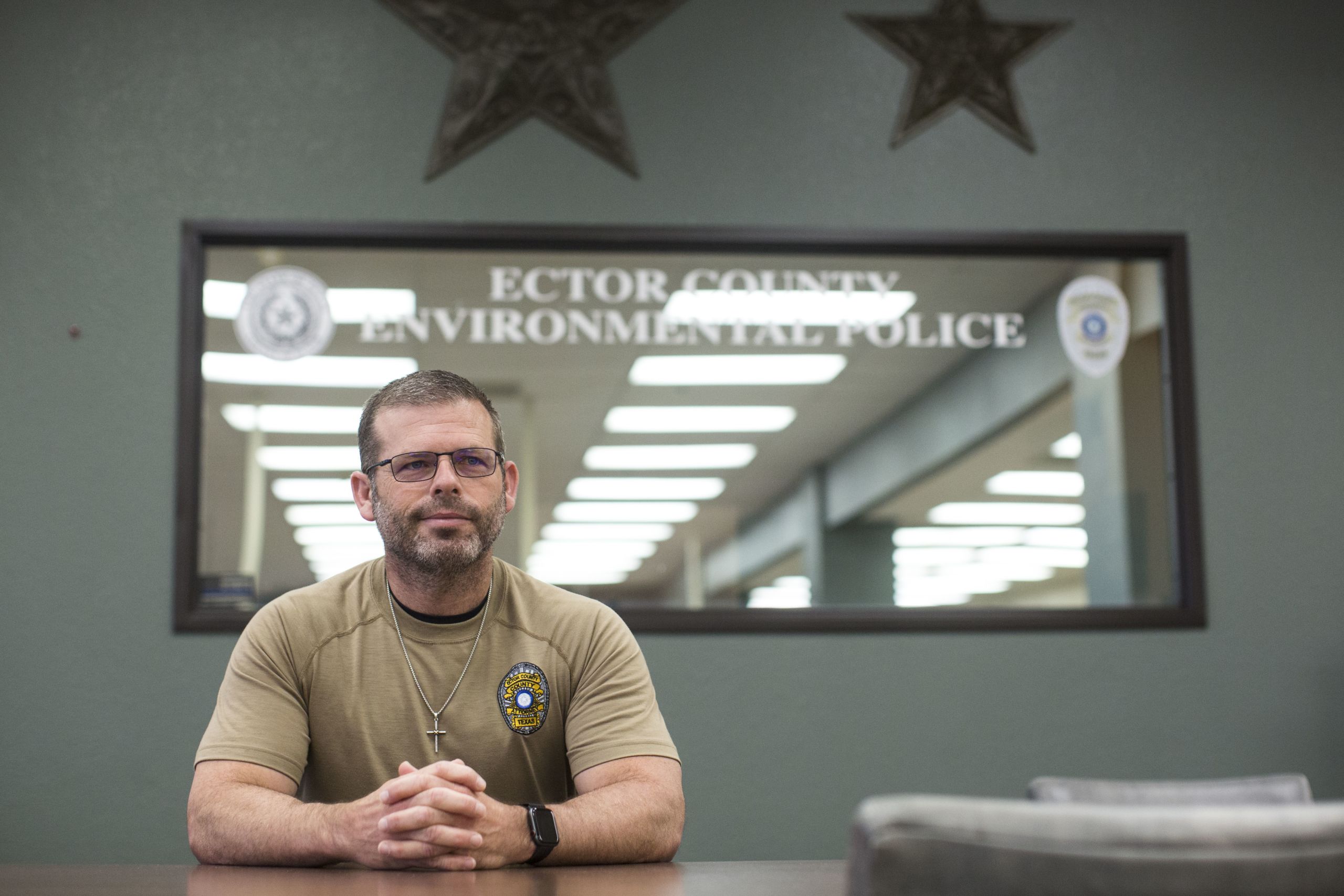

An oil rig outside of Midland, TX. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

An oil rig outside of Midland, TX. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/Texas Standard

Originally published, September 20, 2019

By Alexandra Hart

A new space race of sorts is shaping up in West Texas – but not one involving rockets or companies like SpaceX or Virgin Galactic. In this one, energy companies are trying to get as much data as they can from satellites flying over the region to try to keep ahead of their competitors.

Sergio Chapa, a Houston Chronicle energy reporter, says the Permian Basin’s high productivity and competitive environment created a demand for energy companies to pay for satellite images of their competitors’ drilling rigs, hydraulic fracturing crews and pipelines.

“Data is a premium in that oil field,” Chapa says. “Knowing what the other guy is up to is valuable information to have.”

The practice started a year ago, and grew in popularity this summer, he says. Companies around the globe are now providing similar satellite services; the first company to do it, Planet, in San Francisco, currently has around 150 satellites in orbit.

For oil companies drilling in close proximity to their competitors, the satellites can tell them whether the other guy is drilling into the same rock formation underground. They also give oilfield services companies like Halliburton, Schlumberger and Baker Hughes leads on where new drilling wells will be placed so they can grow their businesses, Chapa says.

He says companies prefer satellites because airplanes, by comparison, require more labor to operate. And drones are regulated in a way that makes it hard to freely survey the vast Permian Basin region.

Houston-based oilfield data company, Sourcewater, uses satellites to map water ponds in the Permian Basin. Water is an essential part of the hydraulic fracturing process, which is how much of the region’s fossil fuels are extracted from the ground. Before using satellites, the company would have to locate the ponds in person or through permits. Now, Chapa says, the company can see “frac ponds” as soon as they’re built, weeks to months before any permits are filed.

“They took a big leap,” Chapa says. “They decided … Why wait for the permits? Why do this? They started using satellite imagery and, you know, it paid off.”

Written by Savana Dunning.

For The Permian Basin, Getting Energy To Market Is The Difference Between Boom And Bust

"There's tons of oil coming out of the ground … but if that dries up, and it's already starting to … then you might start seeing some real trouble.”

KUT energy and environment reporter Mose Buchele talks with Host David Brown at the 2019 Texas Tribune Festival. Photo by Rhonda Fanning / Texas Standard

KUT energy and environment reporter Mose Buchele talks with Host David Brown at the 2019 Texas Tribune Festival. Photo by Rhonda Fanning / Texas Standard

Originally published on September 27, 2019

By Michael Marks

There are few factors more influential on the Texas economy, and even on the way government works, than the price of a barrel of oil. A change of a few dollars either way in the price of West Texas Intermediate Crude has a massive effect on the state's financial health. Thanks to historic production in the Permian Basin, the flow of oil has been strong, and production is at near record levels. But how long will the oil boom last, and at what cost?

Mose Buchele, energy and environment reporter for KUT-Austin, says people across the state feel the impact of the energy-driven economic boom – both positive and negative.

“One of the main ways that people are experiencing this outside of West Texas is pipeline construction … sometimes very controversial projects,” Buchele says. “Right here near Austin, we have the Permian Highway Pipeline that's going to be natural gas – a lot of local opposition in some places to that – crude oil pipelines coming in, heading out to the Gulf Coast and then on the Gulf Coast, big shipping investments in petrochemicals.”

Buchele says that by some estimates there is enough natural gas in West Texas to power every home in the state. But because there is no infrastructure to transport it, the gas ends up being flared and ultimately contaminates the environment.

“There's a new pipeline that's just opened up in Corpus Christi,” Buchele says. “This other Permian Highway Pipeline would take that natural gas and bring it to market. The argument in favor is that you'd get away from that waste.”

But some groups of citizens living near pipelines oppose the construction of fossil fuel infrastructure because of climate and environmental concerns, Buchele says.

Though some in Texas have suggested that economic boom conditions in Texas could be permanent, Buchele says industry experts are bracing for a possible bust, at the hands of Wall Street.

“This whole thing has been funded by a lot of investment,” Buchele says. “But the people who made those Investments are not seeing the kinds of returns that they might like to see so far. There's tons of oil coming out of the ground … but if that dries up, and it's already starting to … then you might start seeing some real trouble.”

A lot of the investments were made when the price of a barrel of crude oil was $100, but now that the price is down to about $50, a number of small companies are expected to declare bankruptcy, Buchele says.

“This is one of the reasons you're starting to see more of these consolidations to bigger companies buying up little ones,” Buchele says. “They're trying to find ways to pick out more profit in the margins, but it's all tied to that dollar per barrel. And that's something that no one person can control that. It depends on so many different things that there's always this element of a gamble to it.”

Written by :Antonio Cueto.

As The Energy Boom Moves West, Drivers Face More Danger On The Roads

"Stay alive on 285" is a common refrain among drivers traveling between Pecos, Texas and Carlsbad, New Mexico.

Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon/KUT News

Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon/KUT News

Originally published October 7, 2019

By Rhonda Fanning & Libby Cohen

The most dangerous border in Texas may not be the one that connects the state with Mexico.

Jordan Blum is an energy reporter at the Houston Chronicle. His article, "Texas' Most Dangerous Border Leads To New Mexico," looks at how the oil boom has drastically changed traffic patterns in southeastern New Mexico, where the state meets the Texas border.

"This is essentially the biggest oil boomtown in the world, right now," Blum says.

He says there aren't a lot of roads and infrastructure in an area where most major oil companies are drilling. There’s only two highways that go in and out of the area.

"Highway 285, going from Pecos to Carlsbad, New Mexico, is aptly named 'Death Highway.' They tell people, 'Stay alive on 285,'" Blum says. "I thought it was an exaggeration, but when I was out there, basically everybody says that."

The area is home to more than just energy workers, Blum says. Near Carlsbad, some 200 children are bussed into schools from oil field "man camps" where they live.

Blum says that in the early years of the recent energy boom, most growth in the Permian Basin occurred near Midland and Odessa, in Texas – towns that are accustomed to handling the need for increased infrastructure. But in recent years, the boom has spread to more remote areas.

"New Mexico has an oil and gas history, but never anything like this," Blum says. "And really, they're just not accustomed to it. … A lot of roads need to be built in a very short period of time, and that's just not happening."

Blum says while energy industry leaders in the area are confident the current boom will continue, they’re reluctant to "overbuild" new infrastructure to accommodate that growth.

Written by Shelly Brisbin.

Hill Country Town Picks Up Pieces After Sand Plants Head West

“Sand goes back a long, long way here in Brady,” says Mayor Anthony Groves.

The Momentive Sand Plant was one of seven plants at one point in McCulloch County. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

The Momentive Sand Plant was one of seven plants at one point in McCulloch County. Photo by Gabriel C. Pérez/KUT

Originally published February 5, 2019

By Jimmy Maas, KUT

Texas’ oil and gas industry is seeing a boom — thanks in large part to the relatively new oil-drilling method called fracking. Late last year, Texas oil helped push the country to become the largest producer of crude in the world. Around the same time, however, the boom came to an end for one town in the Hill Country.

If you follow State Highway 71 west, it ends in Brady, a town of about 6,000 people in McCulloch County. The stretch of Hill Country has a unique geology.

“Sand goes back a long, long way here in Brady,” Mayor Anthony Groves says. "I had cousins that worked in the sand plant in the '50s and '60s timeframe, so sand plants have been here for a long, long time."

The sand here has a nickname in the oil industry: Brady Brown. It’s had many uses over the years, but mining operations were turned up a few notches when fracking came into vogue. Sand — good sand — is an essential ingredient for the technique.

“Some people looked at Brady as a mining town, or McCulloch County as a mining county, because of so much of the central steady part of the income came from the sand mines,” Groves says.

The success of fracking — and drillers’ thirst for sand — brought bigger, international mining operations to Brady. Some bought existing mines. Some started new ones. Most bought up neighboring ranchland and deer leases for expansion. Tiny McCulloch County was eventually home to seven sand plants.

Until last November.

“They told everybody no vacation, no nothin’, we have the big guys coming in,” Arturo Aguirre says. "So, they come in, and Tuesday they told us we’re shutting down.”

Texas Oil Production Is High, So Why Are Gas Prices On The Rise, Too?

The oil pumped out of the West Texas ground doesn't end up in your gas tank.

Pexels

Pexels

Originally published February 25, 2019

By Alexandra Hart

Last week, prices at Texas gas pump spiked by 14 cents on average -- the highest weekly average in about two years. At a time when the headlines are full of news about plentiful oil in the Permian Basin, shouldn’t gasoline prices in Texas be on the decline?

Matt Smith, director of commodity research at ClipperData says oil's market price, not the amount being pumped, determines how much gas at the pump costs.

"Well the reason for it. . . is because of the recent rise in oil prices," Smith says. "The oil price move has the biggest impact on the underlying price of gasoline. And we’ve seen oil prices rise about a third since Christmastime, and so this is getting priced into the pump.”

But the rise isn’t over.

“The unfortunate thing is that it works on a lagged basis, so the bad news is we have higher prices ahead of us,” Smith says.